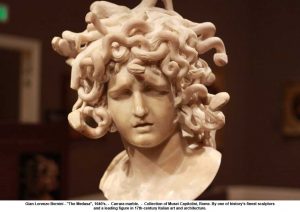

The Medusa Gaze in Contemporary Women’s Fiction: Petrifying, Maternal and Redemptive, by Gillian M. E. Alban. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017. 282p. ISBN 978-1-4438-9148-6

In The Medusa Gaze, Gillian M. E. Alban continues the application of mythological lenses to contemporary literature that she established in her first book, Melusine the Serpent Goddess in A. S. Byatt’s Possession and in Mythology (Lexington Books, 2003). The Medusa Gaze explores the aspects of the snaky-haired figure from Greek myth as she appears in the novels and stories of nine women writers: Angela Carter, Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Sylvia Plath, A. S. Byatt, Jean Rhys, Jeanette Winterson, Michèle Roberts, and Iris Murdoch. The works of these powerful and popular writers span several decades and multiple genres, from romance and realism to modernism and magical realism, but Alban unites them by finding their various engagements with the Medusa figure, an archetype which in her usage transcends historical roots and cultural periods to resonate in our present moment with “an illuminating picture of women’s struggles” [13].

The premises of the book rest on several seeming contradictions which the reader must be able to hold in tension in order to properly appreciate Alban’s assertions. First, though she stakes out her primary texts among female authors writing primarily in the second half of the twentieth century, the reward of pursuing Medusa through their pages rests on the reader’s inclination to find relevance and inspiration in this remnant of “goddess mythology” [7] and one’s ability, through these fictional works, “to re-envision established mindsets” and find “fresh approaches to the lives of women in today’s world” [12]. The power of the Medusa gaze, Alban suggests, is as apparatus of female agency: Medusa’s functions are destructive, maternal, and protective [6-7], and hers is the power to “break free of assigned patriarchal roles” [13] to “form herself and survive through her own gaze” [15]. Alban finds a triumphal interpretation in the original myth in which Medusa, raped by Poseidon, is given her snake hair and death-dealing stare by the pitiless Athena, who later adopts the Gorgon’s head as her aegis. This end, Alban argues, gives Medusa a multidirectional and redemptive power to either protect or destroy as she wishes, and for support she refers to Susan Bowers in “Medusa and the Female Gaze,” who reads Medusa as “an electrifying force representing the dynamic power of the female gaze . . . enabling women to rise above oppression through her inspiration” [qtd. on 2], and Hélène Cixous, who depicts Medusa as beautiful and laughing [23-24].

Following an introduction that “asserts the multifaceted power of women, whether positive or negative, in literature as well as life” [7], the book is structured according to Medusa’s various aspects. Chapters 1 and 2 investigate “the Medusa gaze as a female force” [4] that can empower, objectify, destroy, or—most slippery of all—be refracted by its supposed object back onto its subject and originator, paralyzing and obliterating. Building on Jacques Lacan’s theory of the mirror stage in psychological development, and Jean-Paul Sartre’s use of the Look (le regard) and its power to destroy the Other [20], Alban turns to her primary texts to study how female characters’ use of the gaze in ego formation leads in some examples to an independent sense of self but, in most cases, is ultimately petrifying and destructive to those who wish the gazer harm.

While Chapter 1 identifies instances of “the petrifying gaze of Medusa as exerted by women,” proving “both men and women as objects of a Medusa gaze that destroys through its powerful female agency” [58], Chapter 2 examines instances of “the individual reflected back through the mirror of the Other” [109], the doppelgänger or shadow-self [94]. This chapter, though wide-ranging and entertaining in its observance of mirror-moments, folding Jane Eyre and The Picture of Dorian Gray along with William Thackeray, T. S. Eliot, and J. K. Rowling into the discussion, begins to show the flaws that attend its theoretical underpinnings. Psychoanalytic theory, as a model of mind, can fail to persuasively explain real ruptures in psychic wholeness in terms that correspond to what we know medically about mental health and illness, leaving gaps in the literary interpretation. For instance, the hypothesis, offered here, that a “white model of beauty [is] impressed upon her as normative” [75] seems inadequate to account either for the psychic dissolution of Esther Greenwood in Plath’s The Bell Jar or the violent mental and physical trauma that dismantle the fragile Pecola in Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.

Chapters 3 and 4 of the book “evaluate the joys and perils of mothering” [124]. The connection of maternity and Medusa rests on Sigmund Freud’s speculation that sight of the female genitalia freezes a man in horror, but for the rest of the chapter and in fact the book, the titular figure and her memorable gaze fade into the background of the discussion. Instead, Chapter 3 focuses on “the hazards of the mother-daughter relationship,” finding the dangers “considerable on both sides” [159], and reaches the conclusion that “the trials of mothering are not lightly to be undertaken” [160] from such examples as Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (where the mother character might better be described as intractable, even fanatical, rather than “devouring” [125]), mother absence in Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, and Plath’s poetry, where the discussion veers into the poet’s biography more than her writings.

Chapter 4 draws the maternal goddesses Gaia and Demeter into consideration but continues to explore motherhood as a choice between devouring and abandonment. Those readers who do not already share the assumption that literary characters effectively play out psychological realities, just as mythological figures do, are unlikely to be converted to the psychoanalytic camp by this chapter’s tendency to sketch out fairly broad, universalizing assumptions from the theory and then sift through the literature for support. Alban’s conclusion that the “glorification of the maternal function” doesn’t actually empower women [196] might feel like less a discovery than a statement of fact confirmed by much feminist criticism, but her generous tendency to see most vilified, monstrous mothers as simply overwhelmed by their monumental task strikes a note of compassion and kindness.

Chapter 4 draws the maternal goddesses Gaia and Demeter into consideration but continues to explore motherhood as a choice between devouring and abandonment. Those readers who do not already share the assumption that literary characters effectively play out psychological realities, just as mythological figures do, are unlikely to be converted to the psychoanalytic camp by this chapter’s tendency to sketch out fairly broad, universalizing assumptions from the theory and then sift through the literature for support. Alban’s conclusion that the “glorification of the maternal function” doesn’t actually empower women [196] might feel like less a discovery than a statement of fact confirmed by much feminist criticism, but her generous tendency to see most vilified, monstrous mothers as simply overwhelmed by their monumental task strikes a note of compassion and kindness.

Chapters 5 and 6 expand the Medusa archetype even further to include, in the first instance, “a perspective on the female divine as imagined by women writers” [203] and, in the second, “the common view of woman seen as a predatory, monstrous Medusa” [239]. Alban suggests that veneration of the female divine “creates a paradigm shift in our thinking and changes the way we regard women” [204], offering women readers a process of “symbolization” [207] that can serve as an “inspirational force” [237] in their own lives. Readers might be able to cite counter-examples in which veneration of the female force has not led to appreciable advances in legal, political, or even cultural latitude for women—all of the Middle Ages in Christian Europe, as one example, or contemporary U.S. culture, where women still lack equal protections under the law—but the suggestion is an intriguing one as it applies to fictional role models, especially in these works, where the female protagonists, like Medusa herself, rarely come to happy, healthy ends.

Chapter 6 takes a risk in envisioning Medusa, a figure who in her origin myth is brutally raped and then punished for it, as a femme fatale, but Alban explores “the erotic aura of the magnetic Medusa force” [255] in figures such as Morrison’s Sula, “a monstrous, outlaw woman” [247], flirting with the established belief that female sexual self-expression is perforce predatory or damaging. The real problem with female power as imagined here is that it is only ever reactionary, characterizing women as “opposing male patriarchal power, attempting to empower themselves against the men who oppress them” [243] in a gesture of self-defense and survival. The conclusion reiterates the suggestion that modern readers can find something instructive in these fictional illustrations of “the plight of women, whether aggrandized or diminished, in all their helpless glory” [262], and emphasizes again that “[t]he Medusa force elaborated here presents the ongoing determination of women to claim their rights and assert their will against considerable obstacles, refusing to abjectly submit to the hostile forces that threaten to overwhelm them” [263]. What the conclusion might explain, to further the subject’s relevance to the modern reader’s life, is to elaborate how exactly a woman wields the Medusa stare to her desired effect, whether it be destructive, maternal, redemptive, or apotropaic, deflecting evil intentions back on the perpetrator. Even more useful than the gaze’s function in ego formation would be a stony stare that could, say, repel would-be attackers, cut down cat-callers, or procure a salary offer that equals a man’s.

Alban moves knowledgeably among her several texts and rarely finds it necessary to introduce them with summary, which might pose some disadvantage to readers not familiar with all the texts under discussion. The general lack of transitions can at times lead to a sense of accretion rather than development, an effect unfortunately amplified by the layout of the print copy, which, with its line breaks between each paragraph, suggests continual section breaks in a way that tends to distract from the argument’s evolution. Alban’s habit throughout is to resist analysis or interpretation of any single work, rather letting a text speak for itself through her method of close reading or, in some cases, thick description. While this leaves the reader the interesting task of comparing patterns or drawing conclusions about what any particular work might suggest about self-formation, female relationships, or female agency, certain readers may long for authorial analysis that connects and develops these varied and intriguing works. Throughout, this treatment of primary sources can feel like surveys or extended forays of parallel-finding or pattern-hunting rather than a compelling discovery or developing argument about what exactly these uses of the Medusa gaze might mean, individually or collectively, for the archetype, for the text, or for the reader.

Filled with beautiful original artwork, The Medusa Gaze threads together several marvelous and diverse women authors, providing a sustained and attentive close reading of the female characters’ lives and psyches as girls, friends, lovers, and mothers. In so doing, the book invites a wholesale re-evaluation of the power and beauty of the ancient Medusa myth. If some of the works examined seem to beg for further analysis or investigation into the function or purpose of this mythical figure in contemporary literature, this leaves the door open to future scholars to take up the lens Alban has offered and see what insights about the feminine it may reveal.

Dear Misty,

I have appreciated our interactions over the past few months, and now your thoughtful reading of The Medusa Gaze, offering a detailed response to my book, brightened with stunning Medusa illustrations. I hope you don’t object if I share my reactions to your writing in a reply.

My goddess research and mythic view of the snake appears as way-out to you, as Freudian-obsessed discussion of female castration and penis envy have always appeared to me, never really having been able to understand either. Long before the snakes that fascinate us both were declared phallic, they represented the life force renewing itself in shedding its skin, symbols of the procreative female. Miriam Robbins Dexter cites the Egyptian hieroglyph for the word goddess, “Netreit,” as including symbols of deity and serpent (cited in my Melusine the Serpent Goddess 3). Much remains murky in mythic reflections of women, and without adopting a naive view of women’s position in pre-history, the case for women as once revered as a life force appears overwhelming to me—there is just too much research in this area to discard. I have always regarded women as strong, albeit in an unequal world. My sympathies go with quirkily feminist writers like Angela Carter, who describes the instinctive feminism of the women around her in their “deep, ingrained conviction of the moral superiority of women and the tyrannical economic power of men” (Gordon 95). I therefore refuse victimhood, in common with such as Carter, Atwood, and Morrison. I cite Irigaray’s Speculum in dismissing such self-abjection: why boost male morale by perpetuating fetishization of the male organ? (Medusa Gaze 118).

I really wonder how feminism is advanced by perpetuating the outdated theories of Freud who confessed he didn’t understand women? Feminist theory climbs out of this pit in one generation, only to sink into it yet again in the next. I realize such convictions won’t readily change, and I express my ideas as you retain yours. Aside from that, might I respond to a couple of remarks in your review? You indicate that my argument of “the white model of beauty […] as normative” is inadequate to explain the breakdown of Morrison’s Pecola of The Bluest Eye, as well as for Plath’s Esther. Actually, The Bluest Eye makes a strong attack on the destructive myth of physical beauty which creates gorgeous dolls of suitable women, as I discuss in “Beautified Marionette Dolls,” citing Morrison: “the concept of physical beauty as a virtue is one of the dumbest, most pernicious ideas [… coming from] envy, thriving in insecurity and ending in disillusion” (76, 72) as the sight of the more gorgeous other erodes one’s confidence under their negative gaze” (Medusa Gaze 72). Far better minds than mine have stumbled over Sylvia Plath’s personal traumas (including her own mind) and whatever part of her psyche she may have voiced in Esther of The Bell Jar. In attempting to understand Plath, I access a variety of texts, including poetry and journals, to gain insight into the plight of both the character and the woman writing her; how far I succeed is for you and other readers to say, but the torturous pursuit was utterly fascinating to me.

In a second response, regarding a woman’s questionable ability to repel a rapist’s attack through a Medusa Gaze, I offer Emily Culpepper’s account of how she appropriated the Medusa identity in order to withstand the attack of a rapist: “Seeing her Gorgon self in the mirror, she understands how she managed to gain the power to petrify and beat off her attacker” (256, also page 239, in my “Medusa Fury”). I’m sure it wouldn’t always be effective, but she offers an incident where it clearly helps her. I present such examples in my reading of contemporary women writers in order to indicate the powerful morale women may access when they grasp their own powers, rather than lying down in victimhood. I’m sure my writing won’t enable women to increase their rights or salaries (the part of the world I inhabit is probably far worse than the USA in this respect), but effective ideals may encourage women to grasp what opportunities they can in an unequal world. You’ve done a fantastic job reading my work, and I’m quite sure you could have been a lot harsher on me; I may cede some of your points! I do aspire to reach the common reader, as well as the academic, and I’d go along with making my case through an accretion of evidence. I would be very happy if, as you suggest, further scholars would take up the lens I have offered in continuing studies of the feminine. I appreciate your response, and I’d be really glad if we can continue in collegiality, despite our various differences, with my heartfelt good wishes, Gillian.

Gillian – Thank you so much for your comments! I’m so glad you took the time to comment here and illuminate and refine some of the places where my review missed the mark. I’m always conscious, as a reviewer, that I might not be doing full justice to an author’s work, or might be bringing my own baggage to bear. For example, I’ve long found psychoanalytic theory inadequate as a mode of literary analysis or model of mind, despite how much I loved reading Kristeva, Cixous, and Irigaray as a graduate student.

I have to agree with your point about the unique beauty and power of women in prehistorical myth, and I share the wish expressed in The Medusa Gaze that these stories you examine can provide fresh ways of thinking about women’s power, influence, or choices. After reading your books, I keep running into Medusas everywhere, and am struck anew by the irony that a woman victimized and punished turns into a deathly instrument of revenge as well as a powerful agent for resisting the objectification of women. Here’s to every woman being able to channel her inner Medusa now and again! We need more of her. Thanks again for expanding your thoughts for us here!