I first encountered Angélique Jamail when she posted an invitation to the Facebook group Binders Full of Women Writers for reviews of literature by women, written by women, in the interests of proving that there is indeed a lively literary scene of (and audience for) talented female authors. Aha, I said to myself, this is exactly what Femmeliterate is for! and I signed up. Women Writers Wednesdays are already up and running at Jamail’s blog, Sappho’s Torque (and what a fabulous name for a blog that is), and already providing wonderful suggestions for my to-read list. But then I ran across Jamail’s recently-published novella, asked her for a copy to review (which she gave me! for free! I love this gig), and now have added one more smart, talented female author to my list.

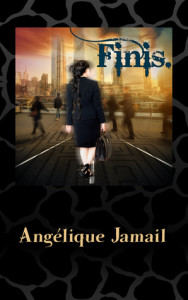

The novella, I think, is a tough form; it seems less a developed form, in fact, than something to call a work of a certain length–more than a short story, but not extensive, layered, or complex enough to merit full-novel-size. But Jamail’s treatment in Finis. shows that the novella can be a complete, developed, and fully-realized gem all on its own. The world she creates, sketched with broad brushstrokes, bears detail that brings it fully to life, and the arc of the protagonist’s struggle is fully explored. If the reader wants more of that world when the book is finished, it is a sign of the intrigue and possibilities Jamail opens up, rather than the signature of an incomplete idea.

Elsa is a young woman faced with challenges that are typical of young adulthood: her job is frustrating rather than rewarding, she can’t afford to live in a posh neighborhood, she doesn’t have an established social group, and among her family, her cousin Gerard is the only one who seems to appreciate and understand her. But in Elsa’s case, these challenges can be explained by a glaring inadequacy that makes her unlike the majority of people around her. In this world, you see, as people mature, they manifest what is called an Animal Affinity. Whether this gives them special powers or is just a physical feature isn’t explained–in Gerard’s case, he certainly likes his water exercises–but what’s more important is how this unique feature serves as a mark of maturity and full adulthood. Those who don’t have a special skill or Animal Affinity–unfortunates like Elsa, called Plain Ones–are subject to all sorts of ostracism and discrimination, everything from the worries or antagonism of embarrassed family members who threaten medical interventions to put-downs from judgmental bosses and co-workers to ravaging packs of brigands who, like wolf packs, roam neighborhoods like Elsa’s and commit violent acts upon the people presumed to be Plain.

I found this metaphor the most engaging part of the story, and I found myself wanting to discuss it with a class. What does it suggest that the fullest realization of one’s humanity–certainly one’s acceptance into the world as a mature adult–is the manifestation of animal features or tendencies? Why do some people seem to resemble more mundane animals, some faintly exotic, and some overtly mythical? (The phoenix is a recurring motif.) How do people manage their relationships with domestic animals–for instance, Elsa’s aggressive cat Jonas, who seems to actively dislike her–if they themselves manifest as part animal, too? What brings about the transformation (it’s not explained, and in one vivid instance, an otherwise Plain woman suddenly sprouts feathers at her desk) and what is the source of derision for the Plains–just the general tendency of social animals to dislike those who are different, or something else? This is the aspect of the novella that invites the most intriguing questions, and the allegorical nature underlines the more direct challenges that Elsa faces, from her job, from her family, from her own sadness about not being a fully-realized Person, as defined by her world.

The well-written prose balances nicely between the tension of Elsa’s struggles and the interest of this world, which other than the animal affinity element seems very much like our own (people keep yards, build swimming pools, eat Salad Nicoise for lunch, have to avoid their boss’s rages or condescension when they are stuck in their jobs), and the final conclusion to Elsa’s journey is satisfying yet still a surprise. She’s a highly relatable character, and her efforts to keep heart against a series of challenges keep the plot engaging and interest high.

So many times I find that stories or other forms that try to create an entirely new world fail on the level of imaginative detail, coherency, or just a general feeling of texture, since so much has to be left out. But Jamail’s world feels fully realized, the arc of the story complete, and the tantalizing questions that remain are due to the deft use of symbolism and the metaphorical implications. I recommend this as a short read that raises many intriguing questions and–in the way that magical realism is supposed to do–reflects tellingly on the world in which we Plain people live.

One thought on “Finis., by Angélique Jamail”

Comments are closed.