Editor’s Note: This post is the third and final in The Feminists are Teaching feature showcasing work done by junior scholars in the Integrative Humanities class taught by Dr. Meriem Pages at Keene State College, Introduction to Thinking and Writing 101: Medieval Women Writers. See Dr. Pages’s introduction for a description of the class and the assignment.

And the Wonder Woman Goes To . . .

By Melissa Depew

When people think of feminists, they picture a lady with a loudspeaker. In a world imploring them to remain silent, feminists raise their voices and will not allow anyone to press their mute button. Modern feminists bellow their message using whatever medium is available: newspapers, blogs, Facebook accounts, graffiti, and more. There was a time when most of these options did not exist, so how did medieval wonder women voice their opinions? Through books, of course!

When people think of feminists, they picture a lady with a loudspeaker. In a world imploring them to remain silent, feminists raise their voices and will not allow anyone to press their mute button. Modern feminists bellow their message using whatever medium is available: newspapers, blogs, Facebook accounts, graffiti, and more. There was a time when most of these options did not exist, so how did medieval wonder women voice their opinions? Through books, of course!

A myriad of medieval women were content to complain about their ex-lovers, call themselves creatures, pit religious icons against one another, or treat female characters as objects in their stories; yet the two contenders for Best Medieval Feminist bucked all of those trends.

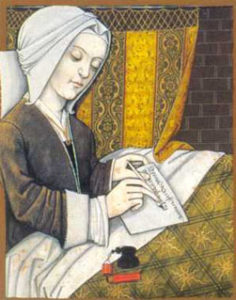

Perpetua faced martyrdom with stoicism and strength while Christine de Pizan wrote a 240-page essay about the virtues of women, validating their value amid rampant and unrelenting bigotry. The fact that their work survives today is a testament to both their skill as writers and the passion behind their message.

Youth is wasted on the young; Heloise wasted hers griping endlessly about her predicament with Abelard far beyond when any normal person would have moved on. Romance was clearly the focus of her young adult life. She did not own up to her choices, and her redemption came too late for any feminist to consider her a role model.

Another woman mired in romance was Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim. Her plays and legends objectified female characters—Drusiana from Calimachus praying for martyrdom as an escape to rape—or omitted them altogether in Pelagius, where the most potentially romantic pair consisted of a tyrant and a captive. Yet, she ignores these issues in favor of condemning non-Christians. She continuously boasted about the superiority of her religion while blinding herself to the secular nature of her own writings.

Hildegard of Bingen pitted Mary against Eve, reasoning that the Virgin should be considered a female Jesus and Eve should be considered a female Satan. Hildegard could have focused on the virtues and vices of women in general—advising them how to increase the former and decrease the latter—yet her musings offered no practical advice for women. She forgot that she and everybody else—including Mary and Jesus—descend from Eve, the so-called cornucopia of corruption. Hildegard refused to see the grayer shades of life in favor of the simplistic, black-versus-white perspective perpetuated by patriarchal thinking at the time. Instead of dividing women against each other, she should have united them to stand together against the rising flood of sexism.

The last medieval woman who will absolutely never be nominated for a Wonder Woman award is Margery Kempe: she eliminated herself in The Book of Margery Kempe. She calls herself a creature and submits to her husband’s bedroom demands. She tries so hard to keep one foot in the world and one foot in Heaven that she trips over her own two feet. She never thought to teach herself how to read and write despite desperately wanting to be a good Christian. What sort of Christian would not pounce at the chance to read the Bible for themselves? Perhaps accusations of being a Lollard terrified her into submission. She should have stood up for her right to read and interpret the Bible for herself. Instead, she spent most of her pilgrimages weeping at the drop of a hat and describing men as good-looking. She cannot even decide whether or not she wants to be with her husband, and most of her visions of Christ involve God telling her what to do, thus making her husband and God interchangeable.

This leaves two nominees still eligible for a Wonder Woman: Christine de Pizan and Perpetua. Which P will leave an MVP? Christine de Pizan has a snappy name and actively argued for women as valid entities. Perpetua simply wrote a diary about her final days. Christine referenced a multitude of sources, foresaw counterarguments to debunk them on her own terms, and utilized an eclectic and effective array of examples in her 240-page essay, The Book of the City of Ladies.

The Passions of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas is a pamphlet by comparison. Perpetua did not even write the work in its entirety on account of being martyred, after all. It is an account of her final days; yet they did not end by her leave, and she remained loyal to her faith.

Christine de Pizan argued that women should only take men’s jobs if men are not available to do them. She would have encouraged women to give up their jobs in the aftermath of World War II and believed that victims should reform their abusers. In the end, quality, not quantity, wins the Wonder Woman. The award goes to Saint Perpetua for a message of strength and conviction: a prisoner of culture will walk free eventually, whether in life or in death.

About the author

Melissa Depew enjoyed her freshman year at Keene State College. While Mel normally writes fantasy stories, a plethora of thought-provoking topics suggested by ITW 101: Medieval Women Writers kept every essay interesting, including, she hopes, hers. Mel looks forward to returning to Keene State in the fall and one day leaving with a writing degree.