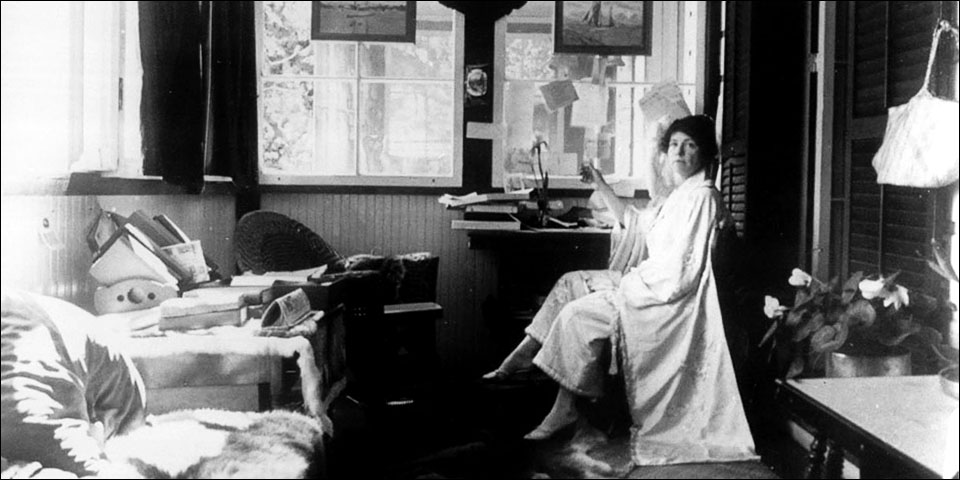

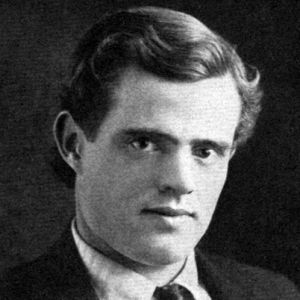

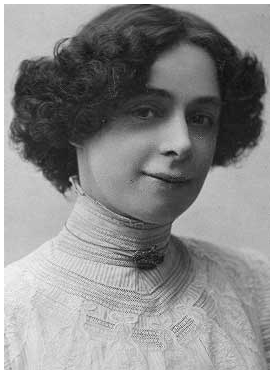

According to biographer Clarice Stasz, Charmian Kittredge London was quite a woman. Born in 1871 and raised by her unconventional aunt, she was a pin-up of the New Woman. She paid her own way through Mills College and got a job as a secretary in a San Francisco firm. She played the piano on the stage and created her own split-legged riding costume to ride astride (no sidesaddle for this lady!). She wrote, she took gorgeous photographs, she traveled, she had an active social life. She was artistic, athletic, intelligent, and utterly unique, and, from the sounds of it, she had no dearth of admirers. In 1904 (when she was 33, a committed old maid!), Jack London—whose book The Son of the Wolf she had reviewed for the magazine she worked for, the Overland Monthly—fell in love with her, left his wife, and made her Mrs. London. And she went, in the public eye then and in our biographies of her now, from being recognized as an extraordinary, independent, talented woman in her own right to being recognized as Jack London’s helpmeet, Mate-Woman, editor, genius loci, and muse.

Like you do.

The wives of famous men are defined by their marriage. There’s just no getting around this. Look up Napoleon. Bio: cunning military strategist, convulsed Europe, made himself Emperor of France. Look up Joséphine or Marie-Lousie. Bio: wife of Napoleon. Fictional biographies follow this same cultural legacy. While the man is defined by his public achievements—grew up on streets of Oakland, sailed to Alaska, wrote books, made scads of money, bought a ranch and sank scads of money into it (that’s London’s bio, by the way)—the woman is defined by her relationships. Charmian Kittredge, wife of Jack London (though she traveled, was also an orphan, also wrote books, helped run afore-mentioned ranch). The standard 30-second biographies will go on to mention her love affairs (of which more later), Baby Joy who died, and then, of her books, first mention of her biography of Jack London. Even Cleopatra is defined by her famous love affairs, and she was queen of two kingdoms, for heaven’s sake. The only historical male I can think of who is defined as consort is Prince Albert, spouse of Queen Victoria.

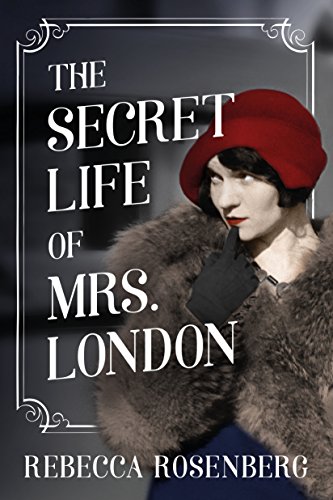

The Secret Life of Mrs. London by Rebecca Rosenberg opens with Jack at its center, and he is Charmian chief’s interest and concern. Chapter 1 begins with a boxing match and ends with a writing session in which we see Charmian taking dictation, making mimeographs, and polishing the big guy’s script for a speech. Part of this is because Charmian loves and believes in and supports her husband, as proper Mate-Women do. Part of this is because she’s hoping for a “grand lolly” (a term I will immediately adopt, in the privacy of my own journal), as most wives who are sexual with their husbands also do. We see right away that Jack is the limit, the boundary, the up, the down, the spur and cinder and chief aggravation of Charmian’s life. It’s a wonderful depiction of the tensions that rise in a marriage when the woman is equal in intelligence, passion, ambition, vision, sensuality, and skill, but is pressed by even his expectations to deploy all her energies in his support.

We also see, in Chapter 1, Charmian receiving come-hither glances from a friend and house guest at Beauty Ranch, a strapping Australian named Lawrence. This brings several other tensions to a simmer. Jack isn’t faithful—should Charmian be? Jack, due to his various ailments, isn’t a satisfying lover anymore, and a woman has needs. Does she have the right to look elsewhere? She doesn’t think so. What Charmian wants, for a good two-thirds of the book, is to have a committed and exclusive relationship with an adoring and energetic husband who will be happy at their ranch with her, their writing, and a baby—yes, a baby, that’s exactly what their marriage needs.

It’s entirely relatable. The secret to this Mrs. London is that she is a warm, cultured woman who enjoys the occasional intellectual squabble and enjoys entertaining guests at reasonable intervals of time, but has had her adventures and now, more than anything, wants domestic tranquility with hubs, baby, his work, and her book, which she’s hoping he will help her get published.

There is nothing, nothing wrong with this. And yet, I confess: I wished Charmian were a little more dashing.

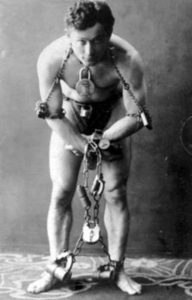

But there is plenty of dashing in the book, and it starts when the Houdinis are introduced. Bess Houdini stole my heart in her first scene. She’s short, sprightly, dressed in some crazy tin soldier outfit, and pops out of the box her husband was bound and chained and locked into. Who wouldn’t love her? (Her given name is Wilhelmina, which means I fell in love with her twice.) This sassy minx struts and postures, tosses out malapropisms like parade candy, carries around a doll of Victoria Woodhull, and does not give two grand lollies what you think of her. Guess what? She, too, is defined by her relationship to a famous man, even though she was her own act before him and continued to be her own act after. So it goes.

But despite Bess’s undeniable appeal, the real scene-stealer in this book is the Great Houdini himself. Rosenberg’s prose is strong and taut, her scenes sleek and composed and crackling, and her plot lacking in sentiment or cliché. But the scenes shimmer when she’s describing Charmian’s Magic Man. Muscular charisma just lights up from that Kindle frame.

Interestingly, Houdini is the least developed of all the characters. We have more insight in the inner life of Jack’s devoted valet Nakata (who is taking a correspondence course to be a dentist) than into the illusionist of world-wide fame. Nevertheless, from the moment of their first meeting, Charmian is fascinated with him, and he is even more fascinated with her. (A reader may, honestly, wonder why; Charmian at this point is spending her time playing nursemaid to an ailing husband, midwife to his work, fretting about being too old to have a baby, and trying to coax her husband to run away to Hawaii with her when Houdini enters the stage.) We don’t see Charmian at her scintillating best, but Houdini does, for he starts sending her secret, coded messages, and Jack finally starts to worry that his Mate-Woman has something going on in her head that doesn’t revolve around him.

[Warning: Spoilers follow.]

Part III is where the book kicks into high gear, for after Jack’s death (and Rosenberg does a great job handling the was-it-suicide-or-uremia controversy, taking advantage of all the novelist’s tools) Charmian finally has a choice to make. Does she want to be Mrs. Jack London for good? Does she want to bear the torch, and the massive expenses of the ranch, and be his literary executor and publicist and heir? Or does she want to be her own woman, write her own books, start her own adventures?

She chooses to have it all, and goes straight to New York to run down Jack’s publisher, peek in on Houdini, have her first ride in an airplane, and pursue her own passions.

This was the Charmian I wanted to see: the woman trying new things, the woman paying attention to the world around her, the woman having friendships and relationships that were not scripted by her powerful husband, the woman who could decide what she wanted and what she liked and whom she was going to sleep with. (Hint: Houdini wins.) She also has to decide if she’s the type of woman who’s going to have an affair with another woman’s husband. The Charmian of this portion of the book is also believable, but she’s far more engaging. She’s grappling with grief, of course, and Jack’s legacies emotional and economic and literary; she’s also in thrall to Houdini’s magnetic charms. (Those eyes!)

The U.S. is also about to enter World War I, but that’s backdrop.

In short, the secret life of Mrs. London is like the secret life of most women, trying to balance the demands of those she loves with the expectations of her culture and the needs of her family and the wishes of her inmost heart. She’s trying to pursue contentment and fulfillment in a world not designed with the contentment or fulfillment of women as its primary or even secondary philosophical goals. She wants her heart to be awake and her body to feel alive. She wants to create something and she wants to connect to others, deeply, meaningfully, nourishingly, well. She wants to express herself and use her talents and enjoy sexual pleasure and yes, damn it, have a baby, and not be exhaustingly, unrelentingly, in sum and in toto Mrs. London, but Charmian, an entity unto herself.

I might be projecting too many of my own preoccupations onto the story here. But Rosenberg’s novel is a wonderful examination of the tensions a famous wife and a talented woman would feel in a world on the brink of collapse, figuratively and in some real ways as well. The writing starts strong and gets stronger, the characters are vibrant and interesting, the settings feel real—I could taste the Hawaiian air again—and there’s a triumphal ending, if not a happy one in the generic sense. I had search screens open all the while I was reading, trying to find out more for myself about the people and their place and time, and Victoria Kelley’s Mrs. Houdini and Charmian’s own books have made their way to my reading list. No better indication that I was completely absorbed in the world of the characters and want to stay there a while longer. What else can we ask our literature to do but make the lives of these lost women accessible to us, and show them as more than consorts but as faceted and complex and conflicted people all their own.