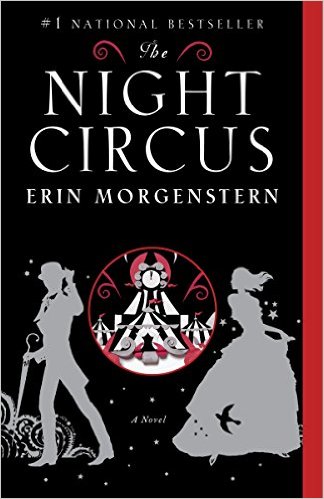

For days after I finished reading Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus, I had to distract myself with other things to keep from breathless reverie. I’m trying to remember the last time I was so affected by a book, and I think it was the first time I read Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone. My reactions to the two are both the same and extremely different.

For days after I finished reading Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus, I had to distract myself with other things to keep from breathless reverie. I’m trying to remember the last time I was so affected by a book, and I think it was the first time I read Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone. My reactions to the two are both the same and extremely different.

When I first read Harry Potter, in 2001 (I was late coming to the series), my enjoyment of the novel and memories of individual, delightful passages were overshadowed by the certainty, deep within myself, that if I could just figure out how to find it, the passage into Rowling’s world would be real. It wouldn’t necessarily be Platform 9 3/4 or even a series of moving bricks in an alley wall in London. It would just be. Even though this book was a children’s novel—tailored in scope, style, genre, and language to a far younger audience—I felt an intimate connection to the story, an overwhelming kinship with the entire concept, for reasons I still cannot entirely articulate. And as I explored the series further, this connection only deepened, both my inner child and my intellectual writer and literary analyst satisfied more and more as Rowling’s series, as her writing, became more sophisticated.

This is not, however, exactly how I felt after reading The Night Circus. I read this book over several nights by the light from my bedside table into the indecent morning hours, when the house was quiet and I could hear every sharp intake of my breath, every involuntary gasp, every sigh drawn from my lungs. My reactions taut as harp strings, plucked.

There is an epigraph in front of the movie The Song of Bernadette, an old film about Bernadette of Lourdes and her mystical visions of the Blessed Virgin, which probably every Catholic of a certain age has seen. The epigraph states that for those who believe, no explanation is needed; for those who do not believe, no explanation is possible. When I listen to people talk about Harry Potter, there is something of this element in their eyes. For fans of that series, often a kind of reverent wistfulness overlays their enthusiasm, a deep-seated desire that Harry be a real person, that Voldemort—either as a true wizard overlord or as simply the embodiment of humanity’s collective fears about their potential to commit unspeakable atrocity—truly can and will be vanquished, and that the key to evil’s undoing might in fact lie in the untested possibility of a very normal kid, one who hasn’t had all the advantages life has to offer. There’s something appealing about that idea, and I think it resonates in young people who care about what they might do with their lives, and it resonates in adults who care about what they are still doing.

There is an epigraph in front of the movie The Song of Bernadette, an old film about Bernadette of Lourdes and her mystical visions of the Blessed Virgin, which probably every Catholic of a certain age has seen. The epigraph states that for those who believe, no explanation is needed; for those who do not believe, no explanation is possible. When I listen to people talk about Harry Potter, there is something of this element in their eyes. For fans of that series, often a kind of reverent wistfulness overlays their enthusiasm, a deep-seated desire that Harry be a real person, that Voldemort—either as a true wizard overlord or as simply the embodiment of humanity’s collective fears about their potential to commit unspeakable atrocity—truly can and will be vanquished, and that the key to evil’s undoing might in fact lie in the untested possibility of a very normal kid, one who hasn’t had all the advantages life has to offer. There’s something appealing about that idea, and I think it resonates in young people who care about what they might do with their lives, and it resonates in adults who care about what they are still doing.

But for those who haven’t experienced Harry Potter, for those who have not been interested in his story, for those who have avoided the books and movies or shunned them for their popularity, no amount of declaiming the virtues of this series will bring any hint of recognition to their faces. Their eyes remain dark and passive. Their bodies take on a slightly bored posture. No explanation of Harry’s greatness can dent their shell of apathy, no enthusiasm can faze their lackluster resolve.

When I finished The Night Circus, I woke my husband and told him, “You have to read this novel.”

When I finished The Night Circus, I woke my husband and told him, “You have to read this novel.”

“I will,” he drowsed from a nest of pillows and comforter.

“Soon,” I insisted.

“I’ll read it soon,” he mumbled, the last of his voice tumbling back into slumber.

I needed someone to talk to about this book, though I had no idea how to begin the conversation. Frankly, I wasn’t sure how long it might take me to digest it all. I toyed with the idea of reading it again, immediately, but I was so emotionally spent from reading it the first time, I wasn’t sure I could handle the overload, not quite yet.

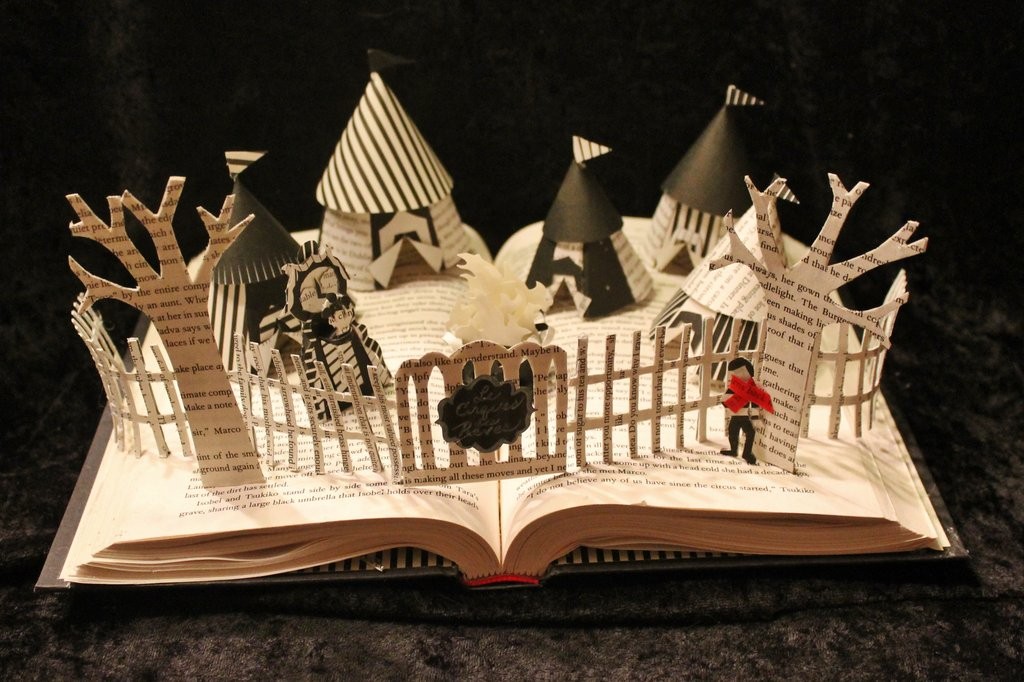

It is not a simple book. The story is non-linear, the prose as nuanced and subtextual as the magic the illusionist protagonists weave to hold their entire world together. The descriptions are thorough and captivating and rich. The points-of-view within the novel shift (though in clear and obvious and important ways). The tensions—all sorts of tensions—between the characters will web around you, suspend you in an elaborate construction of paper and linen, of filament and silk.

In the throes of this novel, I wanted to be inside this world of marvels. I wanted Le Cirque des Rêves to be a real thing, something I could find and attend. I wanted to dress all in black and white with bright red shoes. (And I did.)

But not just for my own amusement and pleasure, I want the possibility of this world to be true, for the world I already know to have the capacity for glorious wonder. I want there to be miracles without judgment and mysteries without fear behind every mundane fold of tent.

I don’t want the fantastical to become commonplace. I want the fantastical to become.

We need fairy tales. They serve a primordial purpose for humanity: the prospect of a life not made bleak by the bounds of reality, by the limitations of the lowest common denominator. As a literary genre, fairy tales have their roots in thousands of years of oral tradition. Called “wonder tales” by scholars, these stories have their ancestral beginnings in the same anthropological need as the Bible, as Homer, as Beowulf, as countless others we read in school when we are young and do not always appreciate until we are older.

The summer she was seven, my daughter read the first two Harry Potter novels for the first time. She has always been an advanced reader, but I worried that she might not be ready for books of that length and complexity. And then late in the evening, long past her bedtime, I would hear her down the hall giggling, exclaiming to herself, “George is so funny! I can’t believe he and Fred did that.” She wasn’t saying this for anyone’s benefit; she was reacting. She was experiencing. No doubt she didn’t catch everything; I didn’t expect her to, not at that age, not on her first reading. But she was feeling the love, and that was more than good enough for me.

So many nights I’ve walked into her room and told her it’s time to stop reading for the night. “You should have been asleep an hour ago,” I’ve said.

“But, Mom! I just can’t sleep! I. Can’t. Stop. Reading!” She assumes her agonized face, eyes crinkled behind her turquoise and lavender glasses, her nose slightly pinched, her head thrown back in frustration.

“You haven’t really tried yet,” I tell her.

But I can’t fault her behavior.

I say, “Get to the end of this chapter, and then go to sleep.” She agrees reluctantly, recognizing this compromise is in her favor.

When I was a child, I stayed up long past my bedtime reading by the slant of closet light across the diagonal of my bed. Most nights my younger brother and I would race to see who could hide out in the bathroom first, where we could lock ourselves in with the bright light, reading for as long as we wanted under the pretense of a stomach ache. Sometimes we could hide there for an hour or more until our parents came and found us.

Winter break is coming. After the rest of my family has gone to sleep, I will still be awake in my bed, reading by the light of a small lamp. I will hopefully have remembered to wear my glasses. I will curl myself around a book in the way that I cannot do with a Kindle, the pages slicing the silence as they turn, cutting away my opportunity for sleep in a desperate hunger for what happens next. The house will be quiet and I will hear every sharp intake of my breath, every involuntary gasp, every sigh drawn from my lungs.

I will not be able to put the book down. I will not be able to sleep. School will resume soon, and with it, mornings that start long before the sun has stretched its light across the sky. Our late nights of reading, losing ourselves in stories while the numbers on the clock grow small, will come to their painful, inevitable end, and at some point in the semester, some part of me will come to the moment in this cycle when I resent that.

But at my core, always, I am a dreamer, a scrap of red life lost in the black and white. I am a rêveuse.

Angélique Jamail’s poetry and essays have appeared in over two dozen anthologies and journals, including Time-Slice (2005), Improbable Worlds (2011), Pluck Magazine (2011), The Milk of Female Kindness: An Anthology of Honest Motherhood (2013), and the upcoming Untameable City: Poems on the Nature of Houston (2015). Her work was selected as a Finalist for the New Letters Prize in Poetry in 2011.

Angélique Jamail’s poetry and essays have appeared in over two dozen anthologies and journals, including Time-Slice (2005), Improbable Worlds (2011), Pluck Magazine (2011), The Milk of Female Kindness: An Anthology of Honest Motherhood (2013), and the upcoming Untameable City: Poems on the Nature of Houston (2015). Her work was selected as a Finalist for the New Letters Prize in Poetry in 2011.  Her magic realism novella Finis. (2014) has been praised by fiction writer Ari Marmell as having “some of the most real people I’ve encountered via text in a long time,” and by poet Marie Marshall as “a witty tale of conformity, prejudice, and transformation, in a world that is disturbing as much for its familiarity as for its strangeness.” An illustrated edition of Finis. will be released late in 2015. She teaches Creative Writing and English at The Kinkaid School in Houston. Find her online at her blog Sappho’s Torque.

Her magic realism novella Finis. (2014) has been praised by fiction writer Ari Marmell as having “some of the most real people I’ve encountered via text in a long time,” and by poet Marie Marshall as “a witty tale of conformity, prejudice, and transformation, in a world that is disturbing as much for its familiarity as for its strangeness.” An illustrated edition of Finis. will be released late in 2015. She teaches Creative Writing and English at The Kinkaid School in Houston. Find her online at her blog Sappho’s Torque.

Thank you so much for hosting me here! 🙂

The pleasure is all ours! So glad to have your lovely words.

“…But for those who haven’t experienced Harry Potter, for those who have not been interested in his story, for those who have avoided the books and movies or shunned them for their popularity, no amount of declaiming the virtues of this series will bring any hint of recognition to their faces. Their eyes remain dark and passive. Their bodies take on a slightly bored posture. No explanation of Harry’s greatness can dent their shell of apathy, no enthusiasm can faze their lackluster resolve…”

Oh Angélique, that really is a cheap crack! There are those of us – many of us, MOST of JKR’s critics in fact – who have delved deep into the HP canon, given it as much latitude as possible, and still find in it literary and thematic flaws you could drive a bus through. And I don’t mean a Knight bus. JKR was fortunate to have had a whole heap of good ideas, to be reasonably articulate, to be sufficiently (but no more than that) talented as a writer, to have a capacity for hard work and a nose for business, to have had a break in publishing, and to have been picked up by a ruthless promotional team. You have to hand it to her – she’s an eminently successful writer. But she’ll never be a great writer. She’s this era’s Salieri, not its Mozart. Take that from someone who has read every one of her HP books, seen every one of the spin-off films, and has herself written for younger readers. [And no, this is not envy speaking. Except maybe for her good looks! LOL]

Anyhow, that wasn’t why you wrote this review. ‘Night Circus’. I am putting aside the thought that if you recommend HP, then this must be comparable. In fact what you are describing here is something completely different. So to that end, I’ll ask you one thing: does ‘Night Circus’ fulfil Flannery O’Connor’s criterion for good fiction, by having an ending that is ‘both inevitable AND surprising’? If it does, it’s head and shoulders above the HP canon, each of which is end-driven and predictable. On that assurance, I will read it.

M.

I think NC is vastly different from HP in many respects and compared here my reactions to them. I don’t know if you’ll find the ending to NC fulfills O’Connor’s criterion, but I found the end to be inevitable and surprising. But then, I like Rowlings’ work, so I might not be the best judge of that for you. 😉 If you read it, I hope you’ll enjoy it.