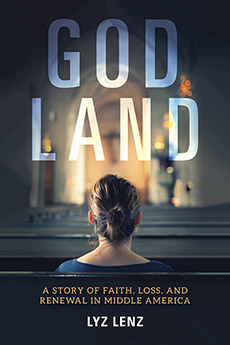

Lenz’s book is a thought-provoking, heart-wrenching investigation into the state of the Christian faith in the Midwestern US, but it is also a poignant quest for a home. Lenz didn’t grow up in the so-called Heartland; she’s a Texas transplant who now lives in Iowa and, with this unique insider-outsider perspective, she perceives the harsh relationship that Midwesterners have with the land. She understands that sense the first white settlers must have felt, of driving across a place that looked benign but felt so huge it could swallow you. She understands lives shaped by the rhythms of seasons and the harshness of drought and flood and storm. Of your livelihood depending on what the land yields in any given harvest, and that only what you wrest from it in sweat and tears.

I’ll say right here that this relationship to land was eye-opening to me. And I grew up in the Midwest. But I grew up in central Wisconsin, in the middle of a patch of sandy soil mined with iron and rich from centuries of glacial deposits, that year after year yielded fragrant green thatches of potatoes and corn and beans, needing no more than the occasional sprinkle of water and dose of pesticides and here and there a year of rest. My relationship with the land is lying in hay fields studded with clover, tramping through forests of birch and white pine, playing in streams choked with rocks and cattails, and walking to the garden to gather dinner from black soil hot from the afternoon sun.

My family didn’t depend on farming to live. But we did go to one of those tiny clapboard churches Lyz describes, with a dozen rows of pews, a bell in the spire, a basement where you could always find powdered coffee and stale cookies. That church was where I went to Sunday school and vacation Bible school, where I learned my prayers, where I first asked the preacher about who Cain married, and where I learned–in keeping with the land around me–that people are good, people will give when you are in need, and if you are one of those gifted with plenty, you always share what you have with others. Anyone and everyone was welcome; there was always enough to go around.

Lenz, transplanted from Texas to South Dakota to Minnesota as a youth, and then arriving in Iowa with her new husband, had a far different experience with Christianity than the Moravian tradition I grew up in. (The Moravians, if anyone is interested, have a fascinating history; they go back to the reformer Jan Hus, who pre-dated Martin Luther. They are a Protestant denomination, and their service looks very Lutheran, though a couple points of doctrine are unique. But I digress.)

Lyz was raised in a tradition more fundamentalist than mainstream Protestantism, and, with her husband, Dave, she attended churches with a very conservative theology. Lyz was the kind of teenager who scribbled Marxist slogans on her T-shirts and was continually being asked not to raise so many questions or be so loud. But she describes, in attending these churches with Dave, how she felt more and more constricted. Silenced. Uncomfortable with policies the church accepted (no women preachers) and the norms they enforced (no gays). She felt less and less room for her.

She wanted to make more room. She looked for different churches. She tried, with some friends, founding a church of their own. (This is a fascinating chapter and I wish there were much more about it. How does one go about founding a church, legally, logistically, spiritually? How you decide what sort of service to offer, what your doctrine will be? How do you form a council or vestry, establish finances and a legal existence, get a tax number, order Bibles and communion wafers? How do you get people to come to your brand-new church? All I took away from this experience was that Lyz invested a lot of time shopping garage sales for chairs and stocking up on coffee.)

I digress again. The point is that Lyz’s efforts at building the kind of church that would have room for her ended up casting her out again. Women weren’t welcome in the decision-making process. They couldn’t be leaders, though they were welcomed as nursery attendants and providers of coffee hour and garage-sale chairs.

The church she helped build evicts her. And her husband, who should be the one person to understand and support her quest, doesn’t. In trying to make more room for herself, Lyz loses her church, her home, her marriage, and very nearly her faith. Her search for belonging costs her everything. And so she sets out to learn why, in this spiritual tradition that is supposed to be for and encompass everyone–to offer a plan of salvation for all God’s creation–there was no place for her.

What she finds, and what she gives us as readers, is no easy explanation of cause and effect, no coherent narrative of the rise and fall of a social institution. But her focused, thematic chapters, beautifully insightful and written in visceral, elegant prose, offer a series of portraits that together reveal what the Midwestern church looks like now. The book will help those who don’t live in the Heartland understand the roots of its conservatism and the principles that preserve it. The book will help those of us who do live in the Heartland, but are only passing acquaintances with evangelical Christianity, understand what is going on in the hearts and minds of our friends and neighbors who join us at PTO meetings and street festivals, school fundraisers and library programs, who chat with us about the school board election and music lessons and soccer league, and then stand in the curtained booth voting against the very principles you would assume, on the face of it, we both share.

Even more than it works as a book that helps Lyz understand why her marriage had to break and her church had to dissolve and she had to tear herself from her own home to be who she is, GOD LAND helps readers understand the paradox that is at the crux of the Midwest: whose people, the salt of the earth, will give the proverbial shirt off their back to a person in need–who will give their time and money to save a community church that isn’t even their own–but who will at the ballet box vote for a xenophobic, misogynistic, racist, narcissistic, unscrupulous president who will set out to attack and destroy every sort of social good and defy every value that the Bible teaches about generosity, kindness, and being good stewards of the earth.

The findings aren’t pretty. They have to do with deep-rooted racism, the kind of inequality that is American’s founding and most enduring, most enshrined principle. Lyz is well aware that the churches constructed by the communities of white settlers who came to wrest their livelihood from the land were built on the clearance of indigenous people, erased in all but name (“Muscatine” might remember the Mascouten tribe, but we can only guess at that). The churches across the Midwest that are dying, their numbers shrinking, their members aging, will blame school sports and deteriorating morals for their vanishing numbers. They won’t admit or can’t understand that the economic and social forces upon which their morals are enshrined–wages that can support a family on a single income, the imperative that women remain in the home as caretakers and unpaid domestic help, and that enduring, pernicious belief that “American” means of white European descent–just don’t work for the majority of us anymore.

70% of the US population may identify as Christian, but a good number of us don’t believe it is immoral or wrong to be gender fluid, trans, or gay; even more of us think women really ought to be treated, and protected, as equal citizens under the law; and a growing number of us don’t see the need to have military-grade weapons in civilian hands, when a regular old .22 will do just as well to scare off the coyote or bobcat or whatever that is menacing your property, in lieu of an AR-15.

But even in the pockets where churches are growing, like the hip megachurches that offer indoor playgrounds and coffee hours and community activities for every age and interest, Lyz notes a prevailing whiteness, and a prevailing white conservatism. They don’t notice it and aren’t called on it, she sees, because there just are no POC there. The “community” they embrace and encourage, replacing doctrine and theology and scripture with inspirational quotes, relaxed decor, and music involving sophisticated sound systems and lights, is fine with being mostly white and traditional-leaning. Fine with not being challenged by the hard messages of Jesus to turn the other cheek, give banquets for the poor, spurn material possessions, and champion the oppressed. I’ve been in these churches, and they’re Chicken Soup for the Soul, not Scripture. And a lot of us are fine with that.

Race isn’t the only prejudice embedded in this lingering Midwest evangelical culture, Lyz finds. There’s still misogyny at the core. Men are the preachers; women make the coffee. There’s a solid distrust for “urban” values and culture; it’s considered a suspect lifestyle. (“City values are sinful!” a pastor’s wife shouts at Lyz at the end of a week-long study session.) The only amorous structure that is condoned, the only family structure that can really be honored, is heteronormative. And non-whites are “other” no matter how many generations they’ve been in the US. Lyz sits in on an Asian worship in a Minnesota church that offers service in 5 non-English languages and where attendance is growing, babies overflowing into the aisle. But this isn’t a change that’s been embraced by the majority of the white parishioners, who merely choose to go to a different shrinking church out of town where the people look more like them.

It’s this essential tribalism that is at the heart of why the Midwest church is dying, why the Midwest itself is suffering population flight to the coasts, and why so many white people voted for Donald Trump even though he made no effort to hide what a terribly inept national leader he would be, your feelings about his personality, business practices, demonstrated beliefs, and conduct aside. It’s a tribalism, Lyz understands, that is shaped by the land and the history of this place, how it was settled by white Europeans. It’s what was imprinted in these early communities to help them survive.

As our survival is more and more in doubt–as we see the effects of climate change in our record heat, our abrasive storms, the thrashing rise of our rivers; as we understand the effects of the toxins we have poured into our water, our soil, our air; as we see our children facing an economic future that has no assurance of security, much less prosperity; and as we daily witness people being shot in their homes, in the street, in school, at the mall, at the hair salon, at their church, sometimes by a destroyed soul and sometimes by the police–our fear and anger are speaking to us more loudly than our principles. It’s hard to feel like sharing when your own livelihood is at risk. It’s difficult to welcome the stranger when you don’t know what harm he might commit, especially if his skin or his culture or his appearance or his faith is different from yours. It’s impossible to give when you don’t feel you have enough, or feel what you do have might be taken away at any moment. It’s safe to admit to the tribe, or circle the wagons, around us and those like us. It is far, far more difficult to open one’s arms to the unknown. To bow to suffering, to choose austerity, to give and never count the cost. To rearrange a society so there is room for all rather than great rewards for a very few and struggle for the rest.

Early Christianity succeeded because the first congregations learned to band together and share their resources to survive. Paul’s letters prove this again and again. Evangelical Christianity in the US feels under threat, Lyz observes; despite the fact that it is the majority religion, that its white members are still the racial majority, and that it is far better represented at all our governmental levels than any other group, the language is that the faith is under attack. Leaders recognize that the mainstream holds a different and more inclusive set of values and that admitting more to the table, especially people with different views, might fracture or diffuse their power. Just like the Inquisition of the Roman Catholic Church, which burned heretics in the name of self-preservation (like it burned good old Jan Hus in 1415), the American Evangelical Church ruthlessly casts out those who do not endorse its “values.” Lyz found this out personally.

Whether this self-selection will lead to starvation any time soon, it’s hard to know. Lyz doesn’t try to give answers. She merely wants us to see what she sees, to sit with it, carefully, attentively, holding all the disparate strands together. And she doesn’t offer false assurance or happy morals or the department store inspirational quotes, either. Thank goodness. Her voice throughout is brash, wounded, confrontational, smart, and unforgivingly inclusive. She makes no apology. She makes no excuses for white privilege. She doesn’t call names or judge. She listens hard. She asks questions. Where she can, she calls out injustice; and where she can’t speak, she swallows a shot of whiskey to go with the fire in her belly. She gives us just the book we need to say, look, this happening here, this isn’t right. But she also shows us a way to hold hands and stand together to weather the changes that are coming.

And the end, I’m glad to say, is hopeful. Lyz is smarter, prettier, more accomplished, and more opinionated than I am, but I’m older, and all throughout the book I wanted to hug her and say, “Lyz, come to my church!” Partly because I would look like a cool kid, bringing Lyz Lenz to service. But mostly because my church–Trinity Episcopal Church in Muscatine, if anyone’s asking–has the kindest, most inclusive, most welcoming heart I have ever seen in a congregation. That church is committed to social justice, and more outreach causes, than any other place I’ve been. I’ve seen that church welcome people of every age, faith, race, ethnicity, citizen status, socioeconomic class, disability, gender, and sexual orientation. Every Sunday (when I’m not teaching Sunday school) I take my place in the pew and listen to a sermon that is generous, heartfelt, and uncompromising in its interpretation of who Christians are and what we do: give, serve, share, minister, be God’s hands and feet in the world. My church doesn’t give messages about how to achieve personal fulfillment or prosperity. Sunday after Sunday, we are instructed in and by the core teachings of Jesus, the original SJW.

That’s the kind of church I grew up in. That’s the kind of church I think of as actually Christian. Any church that calls itself Christian and excludes the outcast of any sort has not adopted the spirit of Christ’s teachings. I cannot, and will not, support a church that teaches prejudice. I hope that kind of church gasps its last soon, and I hope the wounds it has left can heal. I hope Midwestern Christianity starts to look more like my church, and more like the early churches Paul ministered to, in fact. Infused with love. Sharing our bread. Fighting against tyrannical governments and rich oligarchs who wanted to create an ignorant, isolated, deprived underclass of slaves. I want my church to lead the revolution to a better, just, kinder, healthier world. That is the kind of renewal that Middle America needs. This book helped me think about and clarify so many things. Thanks, Lyz. And p.s. you can still come to church with me anytime.

I can’t wait to read the book.

Thanks for the review

Terry – I’ll be interested to hear what you think!

Nice review. (I actually found your review more thought provoking than the book!) I have lived in the midwest all but 8 of my 65 years. Your church and its welcoming attitude toward all people, I believe, is more common than what Lyz has experienced. But what we find is often a reflection of ourselves. We can’t help it! Just as in scientific research, we start out with a hypothesis and then set out to find the data to support it. So we tend to lean toward our original assumptions. Also, our early formative years instill beliefs in us and often continue to unconsciously color our lives in adulthood. I wish Lyz had grown up in a loving, welcoming church such as yours. I hope she takes you up on your invitation.

Shirley, that’s a fascinating observation – “what we find is often a reflection of ourselves.” I’m going to sit with that a while. It casts a new light on the book and it says something important about how we experience the world. And what an incredible value that insight has in understanding other people & their experiences, especially when different from our own. I’m so glad to hear my church is not an oddity. I think their insistence on inclusion, listening, and outreach not only taps into the real message of Christianity but is the single most powerful tool to help us all figure out how to live together in this modern world. P.S. You’re welcome to come visit anytime. 😉

Misty,

I enjoyed, as always, your review of Lyz Lenz’s God Land. I read it to my wife. It spawned a serious, but civil, skirmish in our 28 year discussion about religion.

She grew up in a Missouri Synod Lutheran Church in a small town in Illinois. Her father was on the board of elders, her grandfather, too, and her great-grandfather literally helped build the church. She stopped attending, following a great deal of inner (and some outer) turmoil after the arrival of a rigid, conservative pastor. She concluded that she could not ask her daughters to be part of an organization that relegated women to the status of second-class citizens.

I am a devout atheist (if such a thing is possible) who joined this detested minority in my 20’s, when I concluded that believing in the existence of a loving omnipotent God required one to agree that there is exactly the right amount of suffering in the world. I could not make sense of that.

Missy was intrigued by your church and made the observation that it’s more liberal approach corresponded with what she thought “real Christianity” should be. Were I a Christian I would probably say the same. She insisted that much of her morality was derived from her church attendance as a child but felt that, with the new pastor, her church had drifted away from her. I found this fascinating.

I told her that I felt our sense of morality could not come from religion for the very reason that she could not stay in her church. In other words, the Bible, even the New Testament, is filled with contradictory ideas and philosophies. “The Devil can site scripture for his purposes.”

Most of us do not sacrifice a turtle during a woman’s menstruation, nor do we stone adulterers. Many of us are perplexed by the minutely prescribed dietary laws (clean or unclean, cloven or uncloven) and have some trouble feeling justice was done to Lot’s wife, the “non-prodigal” son, or, even to Cain. There is much in Leviticus that must be simply ignored or winked at in order to live in modern society. Sacrificing your own child on an alter or killing the first-born sons of Egypt is hard to reconcile with Jesus’ encouragement to love thy neighbor. And yet, most religions today, even the liberal ones, drag all that trap along with them out of tradition or the lingering fear of that arbitrary and vindictive Old Testament God.

Obviously, leaving a church because you don’t agree with it’s interpretation of “real Christianity” is a very Lutheran idea – the Lutheran idea, in fact. There is a sharp irony in that, much like Lenz’s sadness at having to leave a church she, herself, helped create.

What it suggests, to a secular humanist like myself, is that our morality is not given to us by religion but is, somehow, innate. We pick those ideas from the Bible which we find agreeable (Jesus’ exhortation to love our fellow man) and reject those distasteful to us (condemnation of homosexuals, the subjugation of women). It’s all in the holy book, though. Some fundamentalists believe it is all true. They mobilize to drive Darwin out of schools and build a giant Ark in the Kentucky hills. But most of us take away from the Bible what we want and reject the rest as allegory, metaphor, or … something. If our morality comes from the Bible how then do we choose what parts of the Bible to celebrate and what parts to scorn.

I sometimes say that the advantage of being an atheist is that we do not have to evangelize. Since we do not believe in souls we have no obligation to save them. Still, we believe in human lives. We believe they should be saved. They should be rescued from stifling oppression, sectarian violence, ridiculous superstition, and intolerant bigotry. We believe girls in Islamic countries should be able to go to school without fear of reprisal. We believe that people should be able to love who they want and form whatever sorts of families make sense to them without persecution.

We too, pick and choose which ideas to celebrate and which to scorn, but we do not feel compelled to call one ancient book infallible, nor even true. We are just as happy to take our ideas from Huckleberry Finn as from the Bible. Jesus’ advice that “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.” is beautiful and precious. So is Huck Finn’s conclusion to “go to hell” rather than betray his dear friend Jim.

.

While I feel sorry for Lenz’s struggle to find a religion that fits her philosophy, there is another way of thinking. To quote Christopher Hitchens:

“We are not immune to the lure of wonder and mystery and awe: we have music and art and literature, and find that the serious ethical dilemmas are better handled by Shakespeare and Tolstoy and Schiller and Dostoyevsky and George Eliot than in the mythical morality tales of the holy books.”

To Femmeliterate readers I would say, humbly: please consider, in addition to the many church options, a non-church one.

Dustin Joy

Dustin – so well put! As ever. Thank you for reminding us all that there are beliefs that lie outside Christianity, just as there are faiths that have little or no relationship to the Hebrew books.

I can wholly empathize and respect Missy’s feeling that a too-strict interpretation forced her out of her church; I’ve gone church-shopping myself in various places, quite aware that in insisting on choosing a community that was supportive and inspiring as well as spiritually enlightening, I was defying some archaic notion of worship that insists on absolute adherence. I’ve often said that I will tolerate the opinion that homosexuality is a sin only from someone who strictly adheres to all the other 400+ detailed laws laid out in the OT, including the dietary ones.

And the secular humanists came precisely to save us from all the premodern bloodshed over precisely those questions of interpretation. Thank God for them (ha ha). I spent decades as a secular humanist myself and came back to a Christian church to get another perspective on the larger questions that entertain me as a writer and a human: how shall one live in the world? How shall one use one’s talents to repair harm, promote love, uphold justice wherever one can? I suspect my attitudes towards the core Christian tenets of salvation mean I am still a secular humanist at heart, and lightning has not yet struck me down.

All this is to say that Lenz’s book hints at, and I wish had gone deeper into, those interpretations of Christianity that license bigotry, intolerance, marginalization, and oppression – all the things the big JC himself basically cleared out the temple and devoted his life to preaching against. I consider these warped interpretations of Christianity responsible for many of our current social ills.

I am not at all qualified to discuss the sources and influences on morality, but I hope you’ll write an essay on it. Or a book. I would buy it, and I would expect it to be autographed.