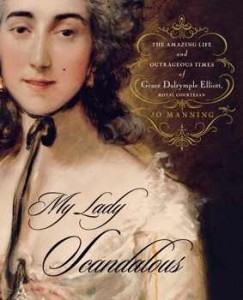

Now, here’s a life just begging for novelization: Scotswoman Grace Dalyrymple Elliott (1754-1823), child bride, scandalous divorcee, courtesan to lords and princes, authoress, and eyewitness survivor of the Reign of Terror, which she wrote about in her incredibly lively and sharply-observed Journal of my Life During the French Revolution (available in its 1859 edition at Cornell University’s archive). Jo Manning’s hefty and deliciously thorough My Lady Scandalous: The Amazing Life and Outrageous Times of Grace Dalyrymple Elliott pads out the relatively thin documentation of Grace’s life with expert research into the tumultuous times in which she lived, mining late Georgian scandal sheets for news of Grace’s marriage and fall from respectable society, contemporary letters for rumors and reports of her various love affairs with tall, rich, titled men, and the Journal itself for Grace’s exploits and imprisonment during the Revolution. The tale is certainly full of excitement, and proves the maxim that well-behaved women rarely make history (that quote attributed here).

While one can find snippets of Grace’s life at various Internet residences (The Mistress Manifesto blog and The Duchess of Devonshire’s gossip column, for example) Manning’s articulate and imaginative study makes this historical period come alive not just by sketching the highlights of Grace’s life but demonstrating how the mores and customs of late-Georgian life contributed to her remarkable career. Grace was not born wealthy or an aristocrat, which means her husband, the physician John Elliott, several years her senior and apparently a mismatch in terms of personality if not in several other ways, held her to a higher standard of respectability than the high-born, who misbehaved all the time in various public ways. Then again, Dr. Elliott had just enough money to divorce his wife when he believed she was misbehaving, and had the luck to catch his not-so-worldly young wife (so the story goes) being seduced (shades of Clarissa!) by an extremely worldly and insincere rake by the name of–wait for it–Lord Valentia.

This is where the story becomes what it is only due to the historical context of the period, and this is what Manning illustrates so well. Never mind that Dr. Elliott is an unfaithful husband and, at the time of his death, leaves behind several “natural” children. Adultery is okay for a husband but grounds for divorce in a wife. Divorce being a long, difficult, and very expensive process of this time (involving the common court, ecclesiastical courts, and an Act of Parliament), Dr. Elliott undertakes to punish his young bride for her lack of discretion and/or injury to his vanity and pride. An aristocratic woman might be able to recover from a divorce; a lower-class woman might choose bigamy in defiance of the law. But divorce leaves Grace Dalyrymple Elliott with a small annuity, a shredded reputation, and an ex-lover who doesn’t want her (Lord Valentia did not, it hardly needs be said, stay by her side in all this). If it’s 1778 in England and you’re a woman of intelligence, spirit, some renown, and uncommonly statuesque beauty (her sobriquet in the media cartoons was “Dally the Tall”), with no reputation to protect, what are you to do?

Obviously, you put on your best dress, go to a masquerade ball, and snag the eye of an athletic earl (later marquess) of matching stature and hearty appetites. This is the part that Lord Cholmondeley (pronounced CHUM-ly, for those not versed in the peculiarities of upper-crust English speech) will play in Grace’s history. He proves a generous lover and loyal friend. For one thing, he apparently doesn’t mind sharing his high-flyer with his good friend the Prince of Wales (later Regent, later George IV–some friendship, that!). He takes Grace back when she returns to England from a stint in Paris and the keeping of France’s most irresistibly rich (if reportedly not as handsome) prince, the Duc de Chartres, later Duc de Orleans. He raises what might very well be their daughter, Georgianna, with his own children (though Grace claimed that Prince George was her father and received an annuity from said Prince in acknowledgement of this supposed paternity). He even pays for Grace’s funeral long after the bloom of their romance is over. Now there’s a guy worth catching.

Grace, however, found English society–or English territory–or, perhaps, England men–less to her taste, and according to Manning felt more at home in France, where courtesans were the de rigeur accoutrement of the wealthy man and where Philippe, it is suggested, kept her in the style which she most preferred: a stately home, magnificent gowns, staggering sets of jewels. Who’d turn that down?

If those striking eyebrows and the powdered hair as pictured in the famous Gainsborough portrait don’t quite fire the passions of modern admirers, it nevertheless apparently did the trick for Philippe. He kept Grace among his intimates right up until his own head rolled courtesy of Madame Guillotine (a turnabout some found fair play, considering he cast the deciding vote to execute his cousin, the hapless Louis XVI). Manning takes some liberties here, as well she might, with the outlines of Grace’s life. Was she not just a Royalist sympathizer but a daring spy? (For whom–the English?) Did she send or carry secret messages for non-Republican forces? (The Tribunal thought she did, which led to her imprisonment.) Factor in a well-documented rescue of a bodyguard to the doomed King and Queen, and we see Grace functioning not just as a woman in command of her own sexual power but in command of a great deal of emotional toughness and reserves of cleverness, as well.

Grace Elliott, courtesan, counter-spy, feminist icon? It’s gratifying to see Manning take such care in the research and presentation of her book, to rise above the gossip and conjecture and provide a resonating, deeply interesting portrait of a woman who, in part, became what she was and accomplished what she did because of the historical period to which she was born. This is a woman who apparently made the best she could of whatever situation confronted her, making the choice–at least it would seem now–of following her heart. And Manning has treated her to a sensitive study as every bit as gorgeous as the Gainsborough portrait. May all the heroic and outrageous women of history be so well remembered.