I am beyond thrilled to announce the publication of Melusine’s Footprint: Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth in the Explorations in Medieval Culture series hosted by Brill.

This volume of 20 original critical essays by scholars from across the globe brings together an array of interdisciplinary perspectives, combining feminist, gender, queer, and monster theory, visual culture, film, and art history, comparative literature and cultural studies approaches, and new investigations into Melusine’s valence as a political, chivalric, and religious symbol in addition to her roles as etiquette instructor, metaphor, and cultural myth. The range of scholarship and the new approaches bring a fresh and exciting perspective to this oft-told and wildly popular story. The essays look not just at Melusine’s huge reception among French and German-speaking readers but also probes her translations into Spanish, Middle English, and Dutch as well as examining the uses of her myth in Luxembourg and the parallels to snake women of the Far East.

The volume is co-edited by Misty Urban, Deva F. Kemmis, and Melissa Ridley Elmes, with contributions by Anna Casas Aguilar, Jennifer Alberghini, Frederika Bain, Anna-Lisa Baumeister, Albrecht Classen, Chera A. Cole, Zoë Enstone, Stacey L. Hahn, Ana Pairet, Pit Péporté, Simone Pfleger, Caroline Prud’Homme, Renata Schellenberg, Angela Jane Weisl, Lydia Zeldenrust, and Zifeng Zhao, and a critical afterword by Tania M. Colwell.

Gillian M. E. Alban, author of Melusine the Serpent Goddess in A. S. Byatt’s Possession and in Mythology (2003) and The Medusa Gaze in Contemporary Women’s Fiction: Petrifying, Maternal and Redemptive (2017), had this to say about Melusine’s Footprint:

This magnificent book combines the extensive researches of twenty interdisciplinary scholars who meticulously investigate the eponymous footprint of Melusine from a wide variety of literary as well as artistic approaches. It illustrates how richly this theriomorphic monstrous snake woman has contributed to the culture of so many European countries, including Luxembourg, Germany, and Spain, not to mention France and England. Pairet describes how certain Spanish versions of Melusine’s narrative emphasize her liminality in attempting to silence her sighs and erase “the metonymy of the humanity the flying snake has left behind” (51). Alberghini discusses Coudrette’s The Romans of Partenay as a “quasi-historical/ mythological text” (155), presenting Melusine as an ancestor of Elizabeth Woodville, the wife of Edward IV, alongside her son, the Scottish Geoffrey of the Great Tooth, “a daughter of the [British] Isles” (155). Melusine’s parallel in “serpentine metamorphoses” (282) extends as far afield as China, where Zhao presents Madam White as an Eve-like monstrous femme fatale, in opposition to Nü Wa, a “goddess [who] is possibly the earliest combination of woman and snake in Chinese literature…. Nü Wa has a positive and even savior-like image among the Chinese (293). One merely wonders why Zhao prefers to see Mrs White as a Melusine figure, rather than Nü Wa, in the light of considerable research indicating Melusine’s divine force.

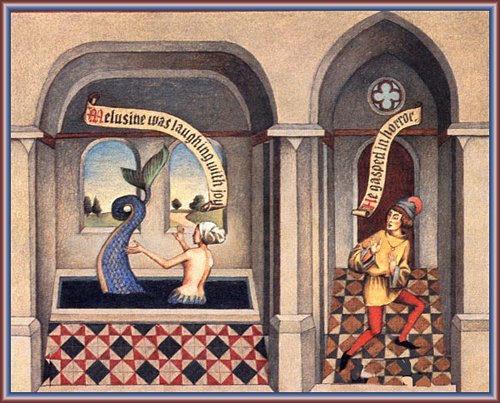

Melusine’s footprint reverberates in her romantic love story with her benevolence and Christian piety, despite her being dreaded and feared by patriarchy. She is represented in her powerfully protective motherhood, which continued beyond her enforced parting as a dragon brought about through male betrayal, leaving her distinctive banshee cri du Mélusine as she stamped her foot in painful distress. Insights into German scholarship reverberate in this study, such as Schellenberg’s discussion of Goethe’s Die Neue Melusine as a Kunstmärchen, to which Goethe compulsively returned throughout his life. Goethe shows Melusine as a victim of betrayal and diminution, a Urphänomen or archetype which he saw as “predicated on visibility…and interconnectedness of disparate phenomena in the natural world” (320). Ridley Elmes elaborates how Paracelsus placed Melusine as an archetype within his alchemical wedding as a “half-human hybrid Melusine figure for the human Aphrodite-Venus form” (100), a transformative figure unifying humanity with nature. Kemmis investigates Bachmann’s “Undine Geht,” alongside the German nixie of the Niebelungenlied and Fouqué’s Undine, also in reference to Grendel’s mother in Beowulf. She presents Bachmann’s Undine’s liquid, wave-like elements, as the nymph’s “call of pain evokes Melusine’s…cri du Mélusine” (337) circling the castle with her uncanny utterance: “I will never come again, never say Yes again and You and Yes” (334). Kemmis also reflects on Kafka’s The Silence of the Sirens, showing the “sirens’ silence [to be] more powerful and deadly a weapon than their singing” (342). Classen’s chapter illustrates various Melusine sirens, fairies and nixies, some of them transformed into chandeliers in Germany. Baumeister develops the Kristevan aspect of Melusine as an abject object of the gaze, also as theorized by Mulvey, showing her “under the gaze of a secret spectator, transform[ed] into a monstrous animal” (362).

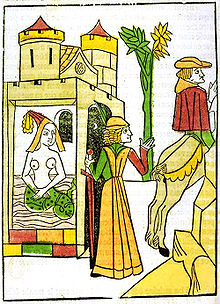

Melusine’s parentage and her punishment of her father Elinas, resulting in her mother Pressine’s curse, which affords her a certain power even as it curses, are extensively evaluated here, together with this liminal creature’s desire to humanize herself through marriage into the chivalric, religious order of her age. Bain describes Melusine as a siren bird-woman while also fish-woman (24), connecting her with Sheela-na-gigs, lamias, and even the Ichthus or fish symbol of “Jesus Christ, son of God, savior” (34), uniting such women within the aquatic. Prud’Homme evaluates Thüring von Ringoltingen’s view of Melusine as both a fair and fairy hybrid, while also an uncanny monster, demonstrated in the odd marks on her sons. Pfleger interprets Thüringen in offering a queer analysis of Melusine’s hebdominal transformations. Hahn unusually processes the tale as exemplifying adolescent insubordination, sibling rivalry and generational discord, showing the violence contained in Melusine’s sons’ chivalrous reach, which needed to be socially contained. Cole shows her as a “Humayn Woman” (240) whose status is secured through her social contributions as she nearly, but not quite, achieved her desired humanity. Enstone points out the fay’s connections with Arthurian legend, developing Harf-Lancner’s parallel study of Morgane and Mélusine together with Nymue, while reworking their Otherness into an ultimately more Christian version. Considerable discussion presents Melusine as a metaphor for transgressive feminine prowess, as represented in her powerful snake aspect, here presented as phallic and therefore oddly as entirely male.

This extensive study clearly indicates the continuing fascination of this most enchanting and threatening seducer. Urban determines Melusine’s Othered femininity, the immense power of this “aerially equipped supernatural female figure who can rule, guide, instruct, build, fight wars, and expand kingdoms” (386). While indicating the absence of many English works on Melusine in the past, she picks out Spenser’s Errour and Milton’s Sin (both an inspiration to A.S. Byatt), together with Keats’ dubious “Lamia,” in her discussion. She illustrates how Byatt’s Possession, and Philippa Gregory’s The White Queen, have revived contemporary interest in Melusine, as a figure who clearly continues to escape prescribed boundaries. Weisl discusses Byatt’s presentation of Melusine’s doubleness as suggesting men’s desires and fears, as seen in the terrifying vagina dentate. Overstepping human boundaries, Melusine becomes a “Scylla, Weird Sister, Lilith (“die erste Eva,” “la mère obscure”), Bertha Mason, or a Gorgon (236), functioning as a monstrous Other in the mirror of romance. Urban similarly connects Melusine with Medusa, this composite figure launching into the future through her appearance in recent films. In Beowulf, Grendel’s mother appears like Melusine, as does the dragon in Maleficent, while in The Clash of the Titans the powerful serpent woman Medusa is shown like Melusine. In sum, this enthralling work contributes extensively to Melusinia, offering devotion to the fairy serpentine hybrid monstrous creature or symbolic force who ultimately never remains contained within any boundaries that may attempt to inscribe her. —Gillian M. E. Alban