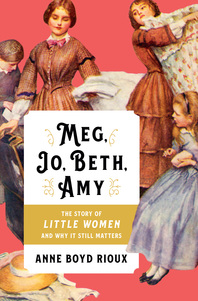

Professor Anne Boyd Rioux shares a lively, informative, and thoughtful life story of Louisa May Alcott’s beloved Little Women in Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters (Norton, 2018). The study contains all the expected elements: a brief biography of Louisa May writing in her attic, the everlasting hunting for parallels between Alcott’s real and fictional family, the analysis of why her book was such a success, and yet another testimony by a young woman who read, loved, and found herself changed by Little Women (which never gets old). But Boyd Rioux offers more. She positions LMA in the evolving field of children’s literature and examines what she was doing that made her book so welcome to audiences; she traces the influences of LW through adaptations in print, music, theatre, and film in the US, UK, and abroad; and she presents sounds reasons for why LW should still be assigned, read, and discussed in schools.

If this seems like a lot to pack in, the book never feels overstuffed. The chapters are focused, tightly structured, and transition well into one another, building a case for a book of remarkable impact and enduring importance. Boyd Rioux’s writing is smooth and completely free of academic cant or hints of scholarly superiority; she’s firmly collegial, even dealing with critics she doesn’t necessarily agree with, and the book is accessible to the peer scholar and the general reader alike. (Norton, as a publisher, has long practice at this, so it’s really no surprise to find the book so accessible, but always a pleasure to encounter in literary criticism). More than that, it’s a lively read; the prose is clean and expressive, her points are interesting and well-grounded, and there’s a warmth for the whole idea of a book about women, for women, that pervades every page.

Of course, readers and fans will approach Boyd Rioux’s book through the lens of their own love affair with Little Women, and it seems time to disclose here that, unlike the majority of other writers who read and loved the book when young, I did not see myself in Jo. I suspected this was a flaw in my character, once I learned that everyone else did. But while I scribbled endlessly in secret, and Jo did so less in secret, and we both had ambitions to be a real writer someday, I was never the fearless, independent-minded, tomboyish, headstrong sprite who did exactly as she wanted and didn’t like people telling her what to do. (Take this quiz to find out which March sister you’d be.)

I identified much more strongly with Meg, the elder, responsible, dutiful one, trying hard to be proper and acceptable and liked, harboring quiet dreams she hardly ever dared express, very conscious that the world was going to demand certain things of her as a young woman (like being sociable and well-liked, attracting a boyfriend, having a successful career), and that she was always in danger of not living up to. Though I lacked her beauty and poise, Meg’s agonies were my agonies. It has greatly contributed to my feelings of imposter syndrome as a writer that I felt such a strong pull to the conventional eldest rather than stubborn, willful, wildly creative LMA prototype, especially when I wanted my own writing career to mimic Louisa May’s in its monetary success.

That aside. Boyd Rioux demonstrates a knack throughout for boiling complexities down to a few salient, summary points that in no way strips them of interest, but makes them very palatable for readers who don’t have the time or inclination to immerse themselves in the growing field of LMA/LW scholarship. In the first part of the book, she fills in the anchor points for the book’s later success and provides the necessary context for understanding how this book came to be what it was. She begins with the circumstances that led LMA to write it (a request from her publisher for a girl’s book—that simple), then discusses how LMA used the context of her own life and experiences to build the story of Marmee and her girls, touching on the lives of father Bronson, mother Abigail, and sisters Anna, Lizzie, and May. She then goes on to discuss the book’s publication history in ways that usefully reflect on its meaning to varied audiences. Whereas US readers know Little Women as a volume that follows the girls from one memorable Christmas morning to their own advances to the threshold of womanhood (or, in poor Beth’s case, not), readers in the UK are generally more familiar with a first volume of LW and tend to avoid, for legitimate reasons, the second, more staid title of Good Wives. Reading LW is a different experience depending on where you get your book.

The second section discussed interpretations and analysis of LW, through its varying adaptations on stage and screen, and this is where Boyd Rioux flexes her critical muscles, distilling broad debates about the book and aptly connecting its various incarnations to the cultural moment of production. She also discusses the book’s use in the classroom as “less of an innocuous family tale and more the kind of book that could ignite uncomfortable discussions” (165), and this sits provocatively side-by-side with her analysis of varying receptions to the major film adaptations, from the LeRoy version (1949) that supports a mandate for American women that “They were to rebuild the population and the economy by marrying, having babies, and filling their homes with new products” (97) to the Armstrong version (1994, and the one you are most familiar with), which demonstrates a “nostalgia for home and family that was particularly potent” (104). This section, in short, moves from a biographical account of the book’s life and times to a powerful overview of the major cultural attitudes of the 20th century in the US. Just a glance at the variety of book covers found by your favorite online search engine will show the huge range of interpretations and variations this story has undergone over the years.

Part 3 of the book pulls out the feminist lens and performs a powerful gender critique, not just on the book, but on our discussions of the book today. Boyd Rioux points out how progressive—or subversive—Alcott actually was in her views about women, supposedly writing at a time when repressive notions of 19th-century femininity and domesticity were at their height. The book depicts a powerful matriarchal and female-centered group with an absent father and concerns that very much center on the girls’ ambitions and self-discovery; Little Women passes the Bechdel test with the highest marks. It shows the girls struggling to contend with the expectations their world put upon them, including Meg’s attempts to adapt to life as wife and mother; Beth, the feminine ideal, receding until she disappears; and Jo, passing up the romantic partner for the smart, stable, professional man who will let her be an equal in running their school and still pursue her writing dreams.

This, essentially, is foundation for the case Boyd Rioux makes for keeping the book in the classroom, and requiring boys to read it as well as girls, however much it’s assumed that boys, who don’t like reading anyway, will hate reading about girls, though girls are expected to read and enjoy Huckleberry Finn and all its avatars. Our own cultural moment, post second-wave feminism, post cultural wars, smack dab in the center of fights over “identity politics,” offers, as Boyd Rioux shows through glances at popular TV shows centered on young women struggling to make their way (Gilmore Girls and the more recent Girls in particular), offers even less choice to young women; instead of encouraging them to grow up and become ‘little women,’ our culture encourages girls to stay adolescent and confused, unable to grow up, and consistently tells them they can’t have Jo’s choice of husband AND useful career AND lifelong creative dream.

As Boyd Rioux writes, “contemporary culture . . . . has a lot of catching up to do. [Y]oung women today need Little Women more than ever, as a counter to the images of womanhood that bombard them” (220). As bizarre as it seems that our culture could have moved backward in some respects in the 150 years since LMA first created her beloved sisters, we do need literary models of “characters moving into a mature womanhood that realizes self-fulfillment and shared joys and responsibilities” (221). Let this be your call, reader, to return to your own worn and dog-eared copy of LW (or an excuse to buy another), and then let it be reason to go create your own tales of women who find success and fulfillment in their ambitions and their relationships, who evolve beyond princesses or fairies or vampires or sex toys, and who have choices beyond which man they marry and how many babies they want to have. I intend to.

Dear reader: Which Little Women character is your favorite? What has the book meant to you? Share your thoughts with us!

When I was about ten years old, my cousin (a year older than I) handed me her paperback copy of LW the first weekend of one summer. “You like to read,” she said, offering me the brick of a book. “Do you want this?” It hadn’t really grabbed her attention, but my interests were piqued. “Yeah, thanks!” I said and took it. I started reading it that day and had finished it a week later. I *loved* it. And reading LW became my start-of-summer ritual that continued for several years, until I knew it so well I could read the entire volume in one weekend. I also read Little Men and Jo’s Boys. This post makes want to not only read Anne Boyd Rioux’s book, but also teach LW to my high school students.

I LOVE the idea of a summer LMA ritual! I confess I return most often to her blood-and-thunder tales, but LW was definitely formative for me. And yes, Boyd Rioux’s book will *definitely* make you want to teach LW wherever possible. She makes such a convincing case for why we need more narratives like this. Thank goodness there are teachers like you & Boyd Rioux who will take on Louisa May!

As Meg is your favorite, I think you’re going to be very happy with how she is portrayed in the Masterpiece series coming up next month. She is finally given her due. I have read Anne Boyd Rioux’s book as well and you said everything I want to say about it. This is a groundbreaking book, bringing together great scholarship with good and relevant storytelling. I was sorry when it ended.

I am very excited about that series, though astonishingly, I didn’t know anything about it until Anne’s book. It will be such a pleasure to be with the March sisters again. I’m glad you enjoyed Anne’s book, too; one can really fall into love with scholarship this grounded and good and, frankly, a pleasure to read.