When Emily Dickinson died in 1886 in Amherst, the town where she had lived all her life, the later years of which were spent as a recluse, she asked her sister Lavinia to burn her books and papers. Thank goodness Vinnie, for years her sister’s only companion in the family home, decided Emily’s poems should be published instead. The person who proved up to the task of sorting the hundreds of scraps of papers in Emily’s difficult hand, many of them cross-hatched and cluttered with variations and alternate words, some of them incomplete, all of them “odd” and “utterly original,” was Mabel Loomis Todd, a cultivated musician, artist, and society leader who was a friend of the family, a writer herself, and also the lover of Austin Dickinson, Emily’s adored older brother.

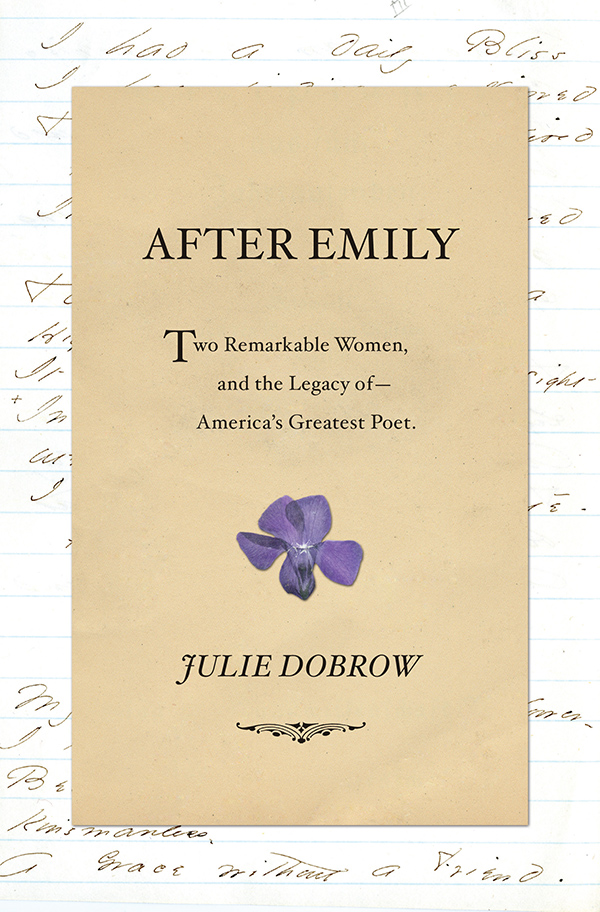

Julie Dobrow’s glorious After Emily is much more than just the story of Mabel’s work to make Emily Dickinson known to the world. It’s a warm, compassionate portrait of Loomis Todd and her daughter, Millicent, who took up the charge to “set things right” after Mabel’s death. It’s a beautifully and thoroughly researched biography detailing the complicated lives, loves, and careers of both women. It untangles the drama between the Dickinsons and the Todds that involved much bitterness, lawsuits, competing claims of ownership, and the resultant scattering of Emily’s papers to different libraries and repositories. It’s an investigation of women who tested the boundaries of their era, a sensitive exploration of a difficult mother-daughter bond, and a glimpse at how the legacy, image, and marketing of Emily were shaped by different champions.

Perhaps most fascinating, it recounts the birth and growth of a literary legend, viewing with generous eyes the stake that several women had in Emily. There is Vinnie, the devoted sister who clung to her own belief of how Emily’s work should be brought to the world. There is Sue Dickinson, Emily’s longtime friend who experienced much tragedy as the wife of her friend’s brother, losing two sons as well as the affection of her husband. And Madame Bianchi, née Mattie Dickinson, who felt her familial claim to her aunt’s work was the greater, even though her competition with Mabel and later Millicent continued to flame old tensions between the families.

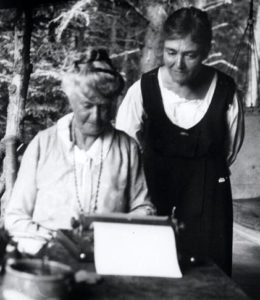

But the bright spot and centerpiece of the book is Mabel, whom Dobrow portrays as a vibrant, energetic, and breathlessly idealistic soul. Many would remember her for one or both of her Dicksinson connections—as the editor of three early volumes of poetry and a two-volume collection of Emily’s letters, and/or as the woman in love with Austin Dickinson, who felt a bond so powerful it transcended death. But Dobrow does her the justice of viewing Mabel as a whole person, getting inside her mind and her affections, noting her wide range of interests and accomplishments; in addition to a career as a public intellectual and popular speaker, Mabel traveled with her husband to several then-exotic locations and brought back reports of them. She was also a patron of the arts and an early conservationist, buying up land so that it could be spared from development, and she conveyed an eye for natural beauty through her paintings, one of which was a gift that delighted Emily.

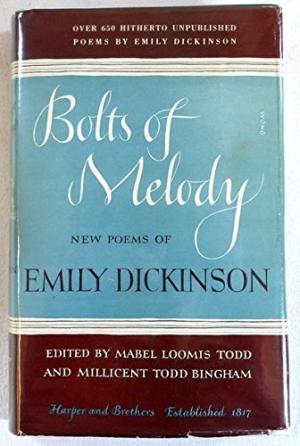

True, Dobrow’s goal is to trace out the elements of Mabel’s life and experiences that made her able to understand and relate to Emily and her poetry; Emily is the absent center lending gravitational weight to the work. But this theme lends the volume a pleasing symmetry, as Dobrow also interprets the life of Mabel’s daughter, Millicent Todd Bingham, through the same lens: her relationship to Emily, compounded by the delicacy of her relationship to her scintillating mother and the burden of the legacy passed on to her to preserve both Emily’s genius and her mother’s considerable investment in the work. Millicent comes across as the sensitive, reserved, brilliant daughter of a brilliant woman and a brilliant, afflicted man who gave up her own promising career as a geographer to bring her mother’s inheritance into print.

No doubt Mabel could be a trial in life and Millicent was difficult to get along with, but Dobrow’s portrayal of both women is insightful, generous, careful, and absolutely wonderful to read, immersing the reader in a world long past where bolts of melody (a line from a Dickinson poem) pierce the mundane and lift the soul to greatness. After Emily is an essential contribution not just to Dickinsonian scholarship but to understanding the forces of a hundred years of American history, forces that shaped the lives of women even as they were shaping the world around them. Dobrow’s beautiful prose is a joy to the ear, her thoughtful relationship to her subjects is delightfully captured, and the peeks throughout into the mind of Emily Dickinson are a revelation, even as her exploration of her two main characters is a valuable addition to women’s biography that will offer much to scholars and pleasure readers alike.