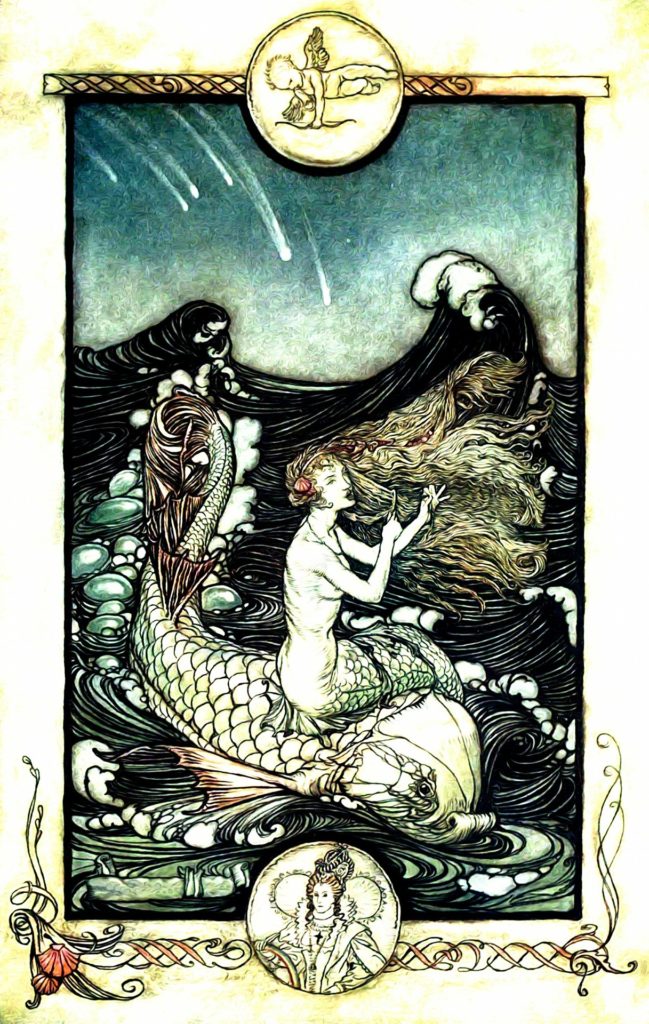

Raise your hand if you’re a water sign and feel an affinity with bodies of water, from the oceanic depths to the puddles that form during rain. Raise your hand if you’re fascinated with watery women: melusines, mermaids, selkies, undines, all those fairy women perched on the edges of magical fountains in medieval romance.

Raise your hand if you’ve enjoyed Angélique Jamail‘s previous contributions to femmeliterate or her novella, Finis., and you’re eager to see her poetry collected in a new book, The Sharp Edges of Water.

There are lovely liquid moments in this collection that will slide down your spine like the princess heading for the ocean trench in “Book With Forgotten Title,” her wet dress, her “headfirst slow descent / through tangled water,” a “disappearance into nothing.” The “strips of kelp / like long wanderings of ripped silk / hung in a breeze.” In “Listening for Atlantis” this same princess looks around her realm with wondering eyes: “Down this deep . . . The light granular, spotted / by sand” is “More than quiet . . . a narrow trench of silence.” She imagines grinding pearls to spice under her bare feet. “In the foam-green light, / a seahorse, reluctant, divines his way / toward me.” The poem itself is “an ecology of the mystical and mundane,” the princess “an eddy, a pilgrim in the deepening dusk of loss.” Who wouldn’t want to linger in this haunted, beautiful realm, where every silent expression vibrates with meaning?

But this is not a collection that drowns the reader in the mystic. As one poem tells us, “The Modern Woman’s Guide to Modern Life:” “It has been made quiet clear that the world / is no longer safe for fairy tales.” This is the princess, returned, to tell her younger self in “Plan B” “not to whine for help, / but to keep her freedom for longer” by fetching the golden ball for herself, foregoing all frogs. This princess swims alone and is not afraid to show her real shape to the prince, who “will not swim with me, but he waits on the beach / each night, holding the cape . . . when I, wet / and cold and still strange to him, emerge from the cold / water, my legs splitting from the dark sea into pale flesh, / discarded scales dripping into my briny bath.”

These water poems envelop, refresh, and infuse the book with a hint of magic. But life in the water world is not what this princess seeks. Rather, the siren who emerges from these shimmering poems wants a life on land: she longs for formed things, for the breakfast table with marmalade and toast (“His Ballad at Breakfast”), for solid ground beneath her feet, whether it is “a light-stepped waltz across broken-edged marble” (“Barefoot on Marble Fragments”) or “dancing on new floors, trying” (“After” pt. II). She’s headed for the prince and that moment in the chapel when “the veil is lifted and my new life, my new self, breaks into / blossom like a rose made of diamond bursting out of a / rose made of glass” (“Journey”).

It is the earthen world that is the desired realm in these poems, and the images that most linger in the reader’s mind. The things of the earth: hummingbirds, cows, dead cornfields. Earth as a coffin for a beloved cousin. Freeways and car drives, the “long and lonely road” (“Manifest Destiny”), terrain “a flat transgression” (“Two Cities”). From the very first poem with its cinder-block walls and “cracked and peeling / memories” (“Moving Out”) the poet of this book feels most at home not in the cold shimmery depths but the built world and things in it, houses, beds, the jolt of “every scratch and patch / of this decades-old floor” underneath her roller skates (“. . . The Last Roller Rink Left in Houston”).

In fact the prince isn’t the point, either; princes come and go, leave and are left. The most passionate odes and the most lovingly detailed observations are addressed to cities: “O Los Angeles, your . . . shivers and quakes” (“Two Cities”), the “treetops like so much broccoli,” the skylines that “pierce the layer-cake smog,” the mountains “megaliths hazy in jellyfish air, / hulking cloudbanks of deep lavender,” ” the only hills I have” (“Los Angeles”). The knowledge the water-woman seeks in these poems is how to live with feet and a mortal body in a world of earth and sky. The theme is not transformation but journey–the path toward that hazy horizon. And the wisdom the water-woman leaves behind in her last “Letter to My Child / Self” is how to become a creature of the air: “make your bones hard / strong as steel beams / to stretch your delicate / skin across / to cage inside / your bruised heart.”

The juxtaposition is surprising and lovely, and well worth diving into. The poems trace a journey of memories built over time, a demonstration of how the mythic unconscious of our childhood maps onto the fragile desires of our bursting bodies. The poems prick open the hard shell of indifference, endurance, that thick rind the above-world forms on us with all the wounds and cuts and losses of the sharp edges we stumble through and away from. Jamail reminds us to look within for transformation, for “all the nourishing / venom you’ll ever / need.” The lesson is most satisfactory.