Ackmann is well-positioned to deliver this latest lovely entry into the ever-expanding shelf of Dickinson scholarship. She’s loved Emily’s poetry since high school. For years she taught a seminar on the poet for Mount Holyoke College, held in one of the Dickinson houses. And her access to Amherst and its environments gives her a rich insight in the world Emily came from, its landscape, its seasons, its vistas, and its people, criss-crossing that landscape with their varied hopes and dreams.

For that reason, These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson feels more rich and vibrant than the typical biography, and is a more rewarding read. From Chapter One, when Professor Ebeneezer Snell rises to observe the weather, the reader understands that Ackmann is going to approach Emily not through her poetry, as most biographers do, but through her world. And by tracing the outside contours, her relationships, her movements, and her thoughts, she’ll burrow down to the “extraordinary inner world” (xiii) that gave rise to the poetry.

Also unique is that Ackmann isn’t attempting a comprehensive arc of the poet’s life. She is instead interested in a fragment, a moment, that “concentrates, extracts, and distills Dickinson’s evolution as a poet” (xiv). Ackmann selects ten of these distilled essences and studies them in chronological order, and the path she plots allows two equally rich investigations: she can put each pivotal moment in conversation with what came after and before, knitting connections where needed, but she can also plunge into a deep discovery of Emily’s turmoils, loves, anxieties, ambitions, and joys in any given moment, situating them in a rich context that makes the poet feel more real and accessible than past biographies have made her.

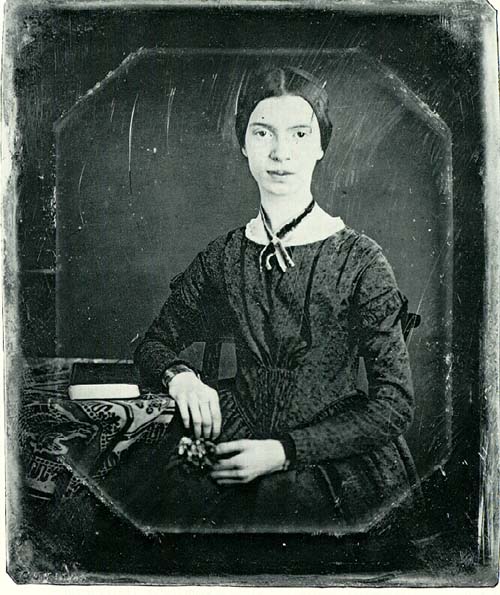

This approach allows a new Emily to emerge, one I’ve never encountered. First, Ackmann doesn’t treat Emily’s famous reclusiveness as an awkwardness that must be worked around or a flaw to be explained. She views Emily’s preference for solitude as the undergirding of her imagination–what allows her to observe and experience so deeply, and then compress such startling images. Her Emily feels “unleashed” by solitude: “being alone set loose in her a potent force” (3). She describes Emily’s desk as “an altar . . . a shrine not to God, but to words” (7). She understands Emily as someone who hid away her powerful experiences until she could think on them. For Ackmann, Emily’s introversion and introspection is not the impoverishment or limitation that so many biographers find it to be. Her Emily is “at turns philosophical and restless,” with high standards (24), who has “confidence, independence, and self-awareness growing in her” (25). The inward-dwelling for which Emily is legendary is not a sad curbing of her power, but the very source of it. She’s “solitary . . . but not detached” (72).

Ackmann’s Emily, also surprisingly, is not timid of publication or too modest for fame, as some biographers portray her. Rather, Emily’s ambition is enormous. “She wanted to be brilliant,” Ackmann asserts. “She wanted fame” (77). But she wanted it on her own terms. She wasn’t out to please readers or earn a living; her ambitions were more fierce than that. “She wanted her poems to translate all she saw and heard and felt, and not be any earthly thing. What she aimed for was evanescence like the brilliance of lightning, the flash of truth, or a transport so swift it felt like flight” (87).

This image of Emily as a powerful visionary underpins the book, and is its fresh offering to the fountain of Emily studies, just as the concatenation of ten powerful moments are fresh draughts of water to those of us who would have said we knew Dickinson’s life well. We know its outlines, but Ackmann opens up the inner vistas of the woman who lived through and for her poetry. She gives us a young Emily at the piano developing her musical ear; “Music taught her what rhythm, style, and going against the rules could accomplish” (17). She shows us a young writer “coming to understand how to make ideas visible” (18). She glories in Emily’s self-professed wild, hard-hearted, “savage” (63) streak. She describes a personality that longs to be “heard but not seen” (59). And she illuminates a strong, resilient soul who is, to her bones, fearless: “Emily wanted to stare down [the unknown] and walk straight into the abyss” (46).

The power Ackmann captures in distilling these moments, along with the often poetic lifts to the prose, make this biography a thrilling read, hard to put down. At its center is a study of the poetry and how Emily approached her poetry–her philosophy about her “poetizing” (72), her cautiousness around publication, and her relentless, exacting revision, as shown in her approach to “Safe in their alabaster chambers” (102-3). Far from a timid soul fearful of rejection, Ackmann portrays Emily as a tireless workhorse dedicated to perfecting her craft, reworking lines and images for months and even years until she got it exactly right. It wasn’t that she was afraid of how the world would regard her poetry; she was working to reach her full power. “Her devotion was to the work itself, not the world,” Ackmann explains of her stinginess in sharing her words (206). She was striving, as she wrote once to her beloved sister-in-law Sue, for “taller feet” (111).

In addition to her familiarity with the landscape of Emily’s life, Ackmann’s footnotes show her comfort with previous biographies and her congenial relationships with current scholars, including other researchers and archivists. The richest part of the book–even more than her careful and intuitive reading of the poetry–is her facility with Emily’s letters. These, sometimes as much as and sometimes more so than her poetry, provide a glimpse into Emily’s soul. They also reveal that her “poetizing” wasn’t limited to stanzas. The sheer, “singing” voice of the poet (122) often bounds out of her letters, as when she asks Higginson if her verse “is alive” (131). As when she says of fame, being cagey for a moment, “My Barefoot-Rank is better” (138). And those immortal lines about how poetry makes her feel cold, and as if the top of her head were coming off–those were said in conversation with her mentor and devoted friend Higginson, one of the few occasions they met. Emily’s poetry wasn’t confined to the page. Rather, Ackmann’s biography reveals it for what it was, the outgrowth of the way this particular person looked at and lived in the world.

In whole, Ackmann’s approach of meditating on a single moment that spreads in ripples to other parts of Emily’s life yields discussion that is rich, delicious, and deeply moving. The prose itself turns toward poetry in many places, perhaps most when dealing with the challenges and heartbreaks of Emily’s life: when she feared she was losing her eyesight; when Amherst’s beloved boy Frasar Stearns was killed in the Civil War; when the deaths followed of her father, her darling nephew Gib, several of her childhood friends, and her late-in-life-love, Judge Lord. Ackmann renders for us a deeper, fuller understanding of the woman who created this resonant, astonishing poetry, and the slow patient sculpting of her emergence, the compassionate plotting of her evolution and her impact, make this biography not just a fitting tribute to its subject but useful ground for understanding and approaching the poetry. “Emily’s words were unparalleled,” Ackmann concludes, “–gleaming, startling, and rapturous” (232). So is this book.