Or: Why Feminism Needs to Be Mainstream, Reason #147.

I just dropped my daughter off for the first day at her new preschool. I realize it’s summer, which may amplify the immediate clutch of guilt, worry, shame, and deep ambivalence I felt. It doesn’t help that the two year old has been asking, in a plaintive voice, for his sister. The instant I walked out the door, to attend to the small things that followed–turning in the paperwork to get me hired at the local college so I can teach in the fall; procuring the morning mocha; sitting down to draft this column–the small voice began: What are you doing? You could be doing this with your daughter. You didn’t need to unload her at school to get this done. You are a terrible mother and a terrible person and this just proves it.

Whence this terrible, crushing guilt? The preschool is a great facility. The teachers are wonderful and the curriculum is founded on extensive research into early childhood development, which is way better than what she gets at home. This will be good for her, and it gains me time to write, which I love to do almost as much as (maybe as much?) as I love my daughter. In a few weeks my son will start daycare and I’ll feel the same internal storm of guilt, relief, shame, and selfishness except doubly, or exponentially, so as I scurry to my office and the projects piling up there. I will survive the guilt and they will survive the daycare. So why can I not make peace with myself over this?

I’m tempted to ascribe it to my internalizing of a deeply ingrained cultural myth that the Mother is All Things to Her Children. She is the arbiter, the protector, and the great decider about who gets access to and power over her kids. She chooses the babysitter, the dentist, the pediatrician, and the day care. She interviews the piano teacher, swim lesson instructor, and soccer coach. She is in charge of diaper replenishment, keeping up the stock of vitamins and Band-Aids, keeping track of vaccinations and medications. She rules when, where and with whom the child is allowed to play, sleep over, or get in a car. Moreover, she knows at all times where the child has left his or her shoes/backpack/favorite blankie/phone. When she lets anyone else take the child–dad, grandparents, step/bonus/other mom, nanny, foster parents, teachers, the state–she is only temporarily conceding stewardship and still retains the ultimate control at all times. We might and with good reason might need to argue this exclusive and persistent influence, but still, it’s how we behave.

And we also act like we have the right to judge the mother for the reasons, duration, and stewardship she selects. You leave the kids with grandma during the day so you can work at curing cancer? Fine, that’s allowable. You need your husband/wife/boyfriend/domestic partner to watch the kids so you can go get a mammogram? Ok, we’ll allow that, no one would want their kid to see that. What? You asked the 12-year-old across the street to watch your kids so you could go get a pedicure? What kind of mother are you, you rich, thoughtless, selfish bitch?

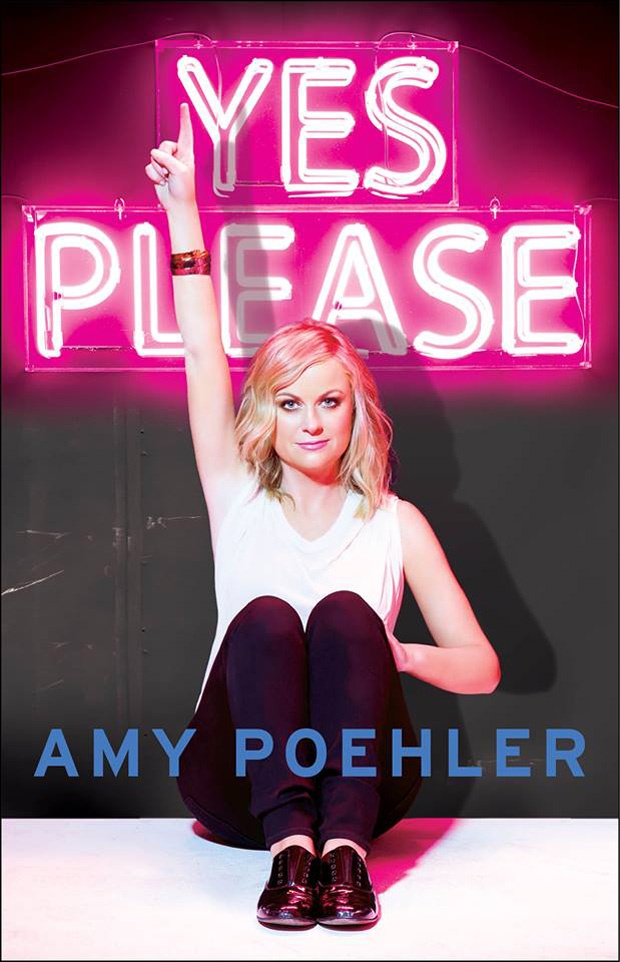

Amy Poehler talks about this in her book Yes Please. There are so many reasons to read this book – because it is hilarious, touching, real, uplifting, full of tiny non-gossipy peeks at loads and loads of celebrities, and also full of pictures, poems, and other Poehler juvenalia that makes me look back on my own childhood with a fonder lens. But her chapter “every mother needs a wife” should be required reading. For everyone.

Poehler (can I call her Amy? – after reading her book and having her confessing, advising, and giggling to me for three straight days, I feel like I should call her Amy) cuts through all the b.s. of the so-called discussion over who’s better, working or stay-at-home mother, with a simple mantra that makes insult and accusation unnecessary: “Good for you, not for me.”

Good for you. Not for me.

Note the grammatical beauty of that. Two simple, declarative statements. Not a subordinating conjunction that would imply preference (like “That’s good for you, but no good for me”). And also not “Not for me, good for you,” which implies something vaguely condescending, a tacked-on apology to a cut. Same number of syllables, linked with equal emphasis. Works for you. Not my thing. We’ll shake hands and go our own ways, wishing each other the best.

“We torture ourselves and we torture each other,” Poehler writes, “and all of it leads to a lot of women-on-women crime” (149). She then gives a list (the book is great for lists) and all mothers on any part of the childcare spectrum have heard or witnessed some aspect of each. Sometimes we don’t mean to judge each other. Sometimes we don’t realize we’re being passive aggressive; sometimes we judge and then immediately feel bad for judging. But there’s that small thought bubble inside us all telling us what’s best for us and our families should, obviously, work for everyone else (because we are secretly good and right and this, clearly, is the superior way of doing things – look how well it’s working for us).

Poehler ends the chapter with the delivered-as-a-joke-but-really-sincere declaration that every mother needs a wife – something my writer friends and I used to say to each other all the time back in graduate school, though what we said was “every writer needs a wife” – but she makes an excellent point:

The women who have helped me have stood in my kitchen and shared their lives. They have made me feel better about working so hard because they work hard too. They are wonderful teachers and caretakers and my children’s lives are richer because they are part of our family. The biggest lie and biggest crime is that we all do this alone and look down on people who don’t.

Can’t we all agree that more eyes on a kid is ultimately better? Doesn’t that at least lower the chances of him running into the street? [152]

It’s a matter of the funny delivery making the truth all the more potent. More eyes are better. Having help when we want to work makes us BETTER MOTHERS. This was the point I clung to. But beyond that, Poehler implies that even while we mothers do act and think like we are The Arbiters of All and everyone else who tends to our children ultimately must bow to us (and maybe they should?) it’s no good thinking we have to do it all by ourselves. Every mother needs a wife.

It would be nice if “Good for you, not for me” could end the “random acts of woman-on-woman violence” (151). If working moms didn’t feel accused or guilty when they choose to distribute their time between kids and a paying job. If otherwise unemployed moms didn’t need to call themselves “full-time moms” as if demanding respect for what they do (don’t they already have the toughest job in the world? Do working moms really somehow shed their identity as parent when they step into the office or onto the movie set?) It really should not be so hard to make different choices and allow that there are many paths toward the same end: a healthy next generation who will pay into the Social Security fund and visit us in the nursing home and come to our funerals when we die.

Feminism demands that we respect every woman’s choice that leads to the well-being of herself and her family. If non-high-powered women could stop resenting or accusing the woman who earns a six-figure salary or travels a lot and misses the occasional school play. If working moms stop feeling guilty every time they meet a mom who left her job to stay home and play with her kids and loves every minute of it, even when the two-year-old poops on the floor. The women who choose to be childless, who prefer it. The mom who leaves her own kids with family in another country so she can earn a paycheck to send back home by caring for another woman’s children. If we could just absorb this – if we could truly live it – we might just be able to call a truce in the so-called Mommy Wars.

N.B. My daughter had a great time at preschool. She’s in the next room making a bead bracelet for herself. My son is napping. I’m writing this column. Today I ran the errands, drafted an essay, wrote this post, and assembled a short story collection to send off to a publisher who asked to see it. Once this post is proofed and published I’ll emerge from my office and be a mom again: take the kids out to dinner and buy them ice cream to celebrate first day of school, supervise my daughter’s piano practice, put together my son’s train track for the 847th time, bathe them, put them to bed, feed the fish, wash the dishes, and run a hot bath feeling like it was a good day. Maybe I’ll even say hi to my husband. You know what? This is a great day. More like this Yes Please.

This was so good for me to read today. Thank you. Sharing.

Yes please! 😉