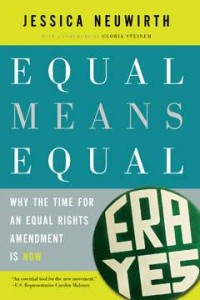

Here’s the perfect gift for the man, woman, feminist, American citizen, or human being on your holiday gift list. But read it yourself first: Equal Means Equal: Why the Time for an Equal Rights Amendment is Now, by Jessica Neuwrith. Introduction by Gloria Steinem. Forthcoming from the New Press in Jan. 2015. Not to be confused with the forthcoming documentary Equal Means Equal, which presumably shares the same message.

The text will outrage–it should outrage any thinking person who even superficially subscribes to the democratic ideals that presumably underwrite this great country of ours, and from which we so sadly, and so widely, and so often fall short in application and practice. It seems so obvious that women should be considered equal citizens under the Constitution, fully in possession of all its sacred rights, subject equally to its full protection. Way back in 1923, shortly after the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, Alice Paul drafted the text of the first Equal Rights Amendment. In 1972, on the heels of second-wave feminism, an ERA passed Congress with the required 2/3 majority. At the time and in the years of ratification, over 60% of polled Americans agreed that the Constitution ought to explicitly grant women all its attendant rights and protections (xvi). In 2001, 72% of respondents already thought women had full constitutional rights (7). In 2012, 91% polled said if an equal rights amendment weren’t already in the Constitution, it should be.

In case you’re wondering, here’s the substantive text of the 1972 version:

Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

It doesn’t seem that inflammatory. Yet in 1982, the window on this amendment closed with only 35 states having ratified it, 3 short of the required. In the subsequent years, despite having no ERA, we have seen all of the fears realized which conservatives and antifeminists used to coordinate resistance to the act of giving women full civil, legal, human rights. Women can, in fact want to fight on the front lines in combat. There are unisex bathrooms. (They are called ‘companion’ or ‘family restrooms,’ and I bless the people who built them every time one turns up exactly where I need it to be.) Gays can, in many states, marry (hurrah for some strides in civil rights!) And the traditional family unit which makes women economically as well as emotionally dependent on men is irrevocably broken, at least as a moral majority or voting bloc; poverty or crime force some families apart while others have the conscious choice to create the domestic structures they feel most conducive to the health and well-being of all involved.

So, in one thread of logic, we might as well have an ERA, since the feminists had their way and have driven us to the brink of social destruction nevertheless. But as Neuwirth shows, we still need an ERA, and if you aren’t completely demoralized after her analysis of why, as well as hopelessly dejected that such an apparently controversial topic as equal rights for women would ever have a chance of support in the even redder, more conservative Congress we may look forward to in January, you will agree with every one of her points, joyfully anticipate your chance to vote, and look for ways to illuminate the remaining 9% of the American public who don’t already think, you know, women are humans too, and should be treated as such.

In truth Neuwirth’s succinct and organized breakdown of the legal histories and precedent behind pay discrimination, pregnancy discrimination, judicial upholding of violence against women–the three main content areas she examines–is rather horrifying. Every time a useful piece of legislation gets passed–Title IX, the Civil Rights Act, the Equal Pay Act, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, or the Violence against Women Act–and a woman brings a case trying to claim its protection, some court somewhere sets to limiting the law as much as possible. Neuwirth tells story after story of how existing elements of the Constitution, such as the 14th Amendement of the equal protection clause, which could be presumed to extend to female citizens as well as male, have been limited by the courts–an astonishing number of times at the Supreme Court level, in fact–to perpetuate embedded inequalities. She clarifies the legal histories in direct, organized, useful ways that make obvious the need for actual, physical language in the Constitution making it inarguably clear that women are granted equal rights and protections.

She devotes the last chapter to examining ways this might happen–try to re-ratify the old ERA through the Supreme Court, leave it up to state ERAs, or just start with a new one? What she doesn’t address–and I don’t blame her–is whether the legislative climate makes any of this possible. 91% of us might believe women should have full and equal legal status; 99% of us might behave as if women already do. But this is America, and that 1% holds a great deal of power–the 1% here comprising, I would guess, our state and federal legislators, courts, judges, lobbyists, Sarah Palins, Phyllis Schaflys, and other conservative talking heads who think while they should have access to every blessing of this democratic country, not everyone else is American like they are.

The fact is, as Neuwirth notes, the U.S. is one of 7 countries that has not ratified the UN Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the international bill of rights for women. It has been ratified by 187 (11). 139 countries in the world have “sex equality provisions in their constitutions” (12). The U.S. does not. In addition, the UN has observed in the U.S. “a lack of legally binding federal provisions providing substantive protection against or prevention of acts of violence against women” and “continued prevalence of violence against women and discriminatory treatment of its victims” (68). One wonders why the supposed global leader and worldwide champion for human rights has such difficulty acknowledging the full humanity of women. Neuwirth doesn’t take on the culture in the U.S.–or at least what appears to be a continued right-wing resistance to the notion of civil rights for anyone who is not historically a white, propertied male as the Constitution originally defined citizenship–to explain why our cherished democratic ideals have not yet, however reluctantly, been extended to the females within our borders. On my pessimistic days–and this is one–it appears to this observer on the ground that, however much we urgently need an ERA in these dark days, we might still have to wait for kinder, gentler, more enlightened times to get it.

But, you still need to read this book. And then, if you want more info, or feel like full civil rights for women is a cause you can get behind, look at the ERA Education Project, the ERA website, or join the ERA Now group on FB, for a start.