News flash for me: post-feminism is a thing. And has been for, like, ten years now. I call myself a feminist, and I didn’t even know my political opinions are already retro? My, my, but life does move fast in this digital age.

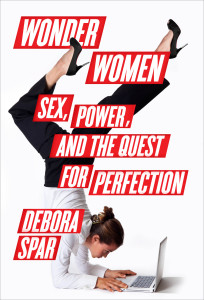

In the spirit of being retro, I would like to submit that we feminists (and women, and female-friendly citizens of the world) should not be done talking about this book. Debora Spar’s Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection has not nearly gotten the press, and the recognition, it deserves. The New York Times book review wanly suggested that Spar doesn’t add much more to the conversation than Sheryl Sandberg of Lean In fame and Anne-Marie Slaughter have done, that she “soft-pedals” her epiphanies and qualifies her vision for the future of feminism. The Washington Post review says Spar’s book “packs less punch” than the above two and bemoans being lectured on collective action by another white, well-paid Baby-Boomer feminist writing a non-revolutionary manifesto. NPR’s interview with Spar on Terry Gross’s “Fresh Air” likewise tames her down with the famous gloved handling that is NPR’s signature (and which, I will admit, I find soothing, even narcotic). Only the Career Girl Network gives Spar her props and a hearty, “Amen, sister!”

This book knocked my socks off. It had me underlining, or exclaiming, or standing up at almost every page, excited to talk to someone about what Spar was telling me. Maybe I’m just too green, not with it (missed the post-feminist boat, after all). I haven’t yet read Sandberg’s let’s-start-a-movement textbook (though I did take due note of the many salient points made by Susan Faludi in her article “Facebook Feminism” for The Baffler). But I had read Slaughter’s article for The Atlantic and in fact my female colleagues and I had been having several discussions–especially as we prepared for and presented a panel on Supermoms for a Women’s Conference–about her precise claims: why are women still being told they “can’t have it all,” or being blamed for “wanting it all,” when what we really want–all most of us have ever wanted–is simple legal, political, and economic equality, on par with men? Why are young women who blatantly and materially benefit from the struggles of their foremothers proudly declaring they’re not feminists (yet still expecting equal pay, a partner who will help out with child care, and the right to occupy public spaces without being harassed, assaulted, or raped)? Why are the goals of feminism continually getting (a) co-opted and (b) obstructed?

For someone asking these very basic questions, then, Spar’s book was revelatory. Her short answer is: feminism got hijacked by consumer capitalism and redirected into a salvational, uniquely American ideal of exceptional individualism that very usefully, and very unfortunately, derailed the collective political work that was gaining momentum for game-changing legislation like the ERA (which, by the way, didn’t pass and still hasn’t, forty years later). Are we okay with this? If we’re adamantly non-feminist but still expect to be able to have a checkbook, own a car, not be discriminated against for pregnancy or childbirth in our paid careers, and be taken seriously if we run for public office, then sure, maybe the issue is a non-starter. For those who are wondering why, after the Equal Pay Act, women still make 77 cents to the male dollar; why, after the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, Peggy Young still has to go to the Supreme Court because UPS fired her; or why Stand Your Ground laws don’t protect women from domestic violence, then Spar has some very interesting things to say. And the crazy-making fact that women in the cultural mainstream simply assume they ought to be treated like equal citizens while still claiming they’re “not feminists” is the very least of the other crazy-making movements, that Spar identifies as consequences of the way that “equal rights for women” got turned into a marketing strategy that splintered the feminist movement better than Phyllis Shafly ever did. (Though, if you’re interested, ol’ Phyllis is still out there doing her darnedest to explain why you, as a woman, shouldn’t have equal rights, anyway).

Sure, Spar’s ultimate plea for a “softer, gentler” feminism might be considered “soft-pedaling.” But she’s addressing an audience that needs to realize that, outside the charmed circle of women who have the liberty of falling into the cultural trap of what Spar calls “the quest for perfection” because they aren’t kept in a perpetual state of soul-crushing poverty by other forms of institutionalized misogyny, the face of “feminism” for the mainstream is the kind of radical feminism that the Shafly-style commentators insist will destroy the family (give her shoes and let her out of the kitchen, and just see what happens!). We feminists need to do a much better job of marketing our brand, but along with that, we need to see past how we’re being marketed to. Spar connects a whole range of serious problems confronting girls and women at every stage of their lives–from aisles of pink toys and princess pageants for toddlers to adolescent eating disorders to the hook-up culture that offers sexual stimulation instead of emotional intimacy to the overwhelming number of consumer dollars spent yearly on plastic surgery–and exposes them as corporate-sponsored marketing strategies that take women’s legitimate dreams for self-realization and derails their time, attention, and money into self-improvement rather than collective community action to improve schools, stop domestic violence, or pass useful legislation. She doesn’t play the victimization card or blame the usual suspects–men, the patriarchy, whatever. She says, sanely and rationally–and quite presciently, if you ask me–that it is High Time That Something Be Done.

It’s not enough to just encourage girls to pursue their education and expect, nay demand, to have satisfying careers as well as satisfying domestic arrangements. Boot-strapping is only part of the equation. We need to figure out why, across the board, women don’t fill more than 17% of top positions and don’t make the same salaries once they’re there. We need to reject the contradictory and mutually exclusive expectations placed upon women and instead channel our energy into practical solutions. (Federally subsidized child care, anyone?). We need to drop the narcissism and start thinking about civil rights again, and worry not just about our individual exercise of choice but in winning freedom for all individuals. We need, Spar says, to recover the joy of liberation. That’s revolution enough for me.