Women, as the editors observe in the introduction to Catholic Women Speak, have been an active and vital part of Catholic tradition since Elizabeth first acknowledged the child in Mary’s womb (xxix). We know that the early Christian church survived Roman persecution because women made room in their households for believers to gather, converse, eat, and share meals both sacred and material. Portions of the New Testament known to both Catholic and Protestant traditions would not exist without the letters St. Paul wrote to the women who administered the faith communities in places like Ephesus and Corinth. Their names are like poetry: Priscia, Junia, Phoebe, Lydia.

Women have throughout the history of the Church prophesied and proselytized and been martyred, have headed institutions, founded traditions, guided spiritual groups, established ministries, and been a public face of compassion. (The book gives a partial list of some more famous ones in its Epilogue 185-6).

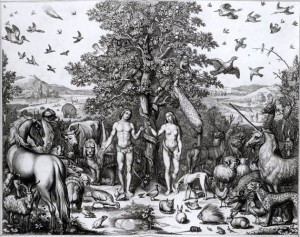

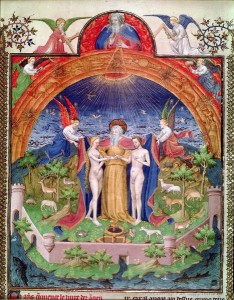

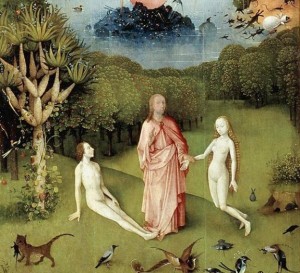

This model of shared participation is reflected in the very first chapter of the very first written record on the subject. In the Genesis of my New Oxford Annotated Bible, 3d ed., God says, “Let us make adam in our image, according to our likeness” (1.26). “So God created humankind in his image, / in the image of God he created them; / male and female he created them” (1.27), and said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply” (1.28).

This scripture, the so-called Priestly account of creation, forms the foundation and core for the Catholic church’s enshrined paradigms of gender complementarity (“male and female he created them”) and the reproductive mandate. Note that in the Priestly version, the male and female are twinned beings, consubstantial, the last and crowning species of God’s great imaginative work, made with and for each other and jointly exhorted to “fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” (1.28). They come into being at the same time, they receive their instructions jointly, they fulfill their shared jobs together.

Then, as has always been the case in scriptural interpretation, author J came along and helpfully thought he would clarify things. The results have been enduringly problematic and also, when read carefully, are a bit silly. For having “formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (2.7), the Lord God—here YHWH—grew some trees, made a garden, and planted man in it “to till it and keep it” (2.16). After pointing out the one tree from which he is not allowed to eat, YHWH decided “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner” (2.18). “So out of the ground the Lord God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them . . . but for the man there was not found a helper as his partner” (2.19-20).

I’m not a proper Biblical scholar, but it seems a bit strange that an omniscient being would not immediately recognize that a compatible mate must derive from the same species. Also, in this version, God begins with man, then makes the plants, then makes the animals, and then parades all living things before Adam. Instead of being the culmination of a grand and beautifully complex biosphere, Adam is the petulant child for whom the rest of Creation is conjured as a toy and a spectacle. Naturally, despite all he is given, the child wants something bigger and better. I imagine the holy father becoming increasingly puzzled and slightly mortified as Adam scans over the flock for his helper/companion and keeps saying “Nope . . . nope . . . nope.”

Finally, in a last ditch effort the Lord God took a rib from his human, made it “into a woman and brought her to the man” (2.22). “Aha!” says Adam, and names her as he named the other beasts brought before him: “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; / this one shall be called Woman” (2.23). This is J’s etiological tale for marriage, as it explains why a man leaves his parents to cleave to his wife, “and they become one flesh” (2.24). It also legitimizes the gendered power differential that has been encoded into the theological DNA of the Catholic church from its inception, and been reproduced in every subsequent institutional promulgation, despite how often the participatory model bears out among the actual practice—and often, the preferences—of believers.

The Catholic Women Speak Network is an online forum for “theological dialogue and collaboration among women” (xvii), drawing on hundreds of members from around the globe and from all varieties of Catholic thought and practice. Editors drawn from this Network organized, collected, and published the essays anthologized in Catholic Women Speak: Bringing Our Gifts to the Table—some reprinted, most new—for the purpose of contributing to the conversations convening around the Fourteenth Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops on the family, which took place in October 2015. (Full documentation of the proceedings are online, for the interested, under the larger work of the Pontificium Consilium pro Familia).

Far more than a scolding of Church leaders, the book provides eloquent evidence that the androcentric nature and history of Church leadership and tradition, in perpetuating an ongoing “refusal and exclusion” of women (13), fails to fully meet the needs of the over one billion members of a living Church, whose real role is not designed as an institution of law-giving but a mirror to reflect the love of Christ to his creation. The chorus of over forty female voices of the contributors, sharing among them an impressive level of education, a number of degrees, and significant service in both the public and domestic realms, while they individually reflect the diversity of Catholic women’s lives, communally call for a “spirituality of inclusion” (xiv), present the humble demand “for a more equal and meaningful presence in the Church,” (9) and imagine “a more just order” (30) that allows a “a full flourishing of humanity” (38) for all of God’s human creatures, not just the prototypical male ones.

The opening essay by Cettina Militello captures briefly but in full the thrust of the argument to follow. She points out that the beliefs of the cultures of the Old Testament, predicated on the subjection of women, influenced a scriptural interpretation of God’s love for humanity that “projects the potential for the divine onto men and the limitations of creation onto women” (7), creating a relationship that is both socially and morally imbalanced. But Jesus’s community was different; his female disciples interacted with him “free of all religious, political, and sexually based submission” (8). The “order of history,” (8) she argues, is responsible for the patriarchal norms that the Church has tried so hard to protect and occludes the real innovation at the heart of Christianity, “equality in the order of grace” (8). “God’s design is fully inclusive” (10), Militello concludes, and while most of the subsequent contributions don’t get specific on the details about how to redesign institutional channels more in tune with the original plan, the rest of the volume echoes this general theme.

The opening essay by Cettina Militello captures briefly but in full the thrust of the argument to follow. She points out that the beliefs of the cultures of the Old Testament, predicated on the subjection of women, influenced a scriptural interpretation of God’s love for humanity that “projects the potential for the divine onto men and the limitations of creation onto women” (7), creating a relationship that is both socially and morally imbalanced. But Jesus’s community was different; his female disciples interacted with him “free of all religious, political, and sexually based submission” (8). The “order of history,” (8) she argues, is responsible for the patriarchal norms that the Church has tried so hard to protect and occludes the real innovation at the heart of Christianity, “equality in the order of grace” (8). “God’s design is fully inclusive” (10), Militello concludes, and while most of the subsequent contributions don’t get specific on the details about how to redesign institutional channels more in tune with the original plan, the rest of the volume echoes this general theme.

The problem, as the second part of the book manifests, is “an extraordinary disconnect” between the formalized Church stance and the “views of ordinary Catholics” (53). As Lisa Sowle Cahill puts it, the laity seek “greater pastoral understanding and flexibility” (59) and “an appropriate adaptation to today’s family realities” (60) on points such as divorce, contraception, marriage, and even homosexuality. Though the authors in this and later sections don’t always agree on how much adaptation or tolerance is necessary, the occasional conflicts improve rather than diminish the conversation.

None of the changes called for are truly drastic; no one goes so far as to suggest that the Church do a revolution and approve Plan B, gay marriage, or divorce. But the authors here offer honest and often touching insights into what it feels like when the Church frowns on the divorce from an abandoning, abusive, or unreliable partner; when one’s non-Catholic spouse must remain in the pew during communion; when the family planning methods approved by the Church cause unnecessary strain, as when abstinence drives a wedge in a couple’s closeness or the rhythm method, failing spectacularly, delivers to a tired mother more children than she feels she can handle.

In cautiously suggesting how the Church might re-examine some of its dictates to be more sensitive to the pains of humanity, the authors draw on a metaphor of the maternal church that has endured since medieval times, an analogy that on close inspection proves hilarious and somewhat jarring when one considers that the maternal instinct has universally and popularly been assigned to the female while the decision-makers of the Church have always been male and celibate. One option for softening the Church might, then, conceivably be to admit women to more institutional roles, bringing with them their historically-granted capacities for tenderness.

But when I hear Pope Francis speak, I don’t doubt for a minute that his eloquence on the subjects of mercy and compassion spring from a wellspring that proves that love is contained and held in the image of Christ just as much as gender differences are supposed to be. While sexual dimorphism might be God’s design, gender roles are human inventions; the imagination of God encompasses a fundamental spiritual equality that profoundly disrupts the cultural and social conventions we’ve inherited, but could be wholly liberating, and certainly much healthier, if we took that as our model instead.

There are, naturally, contributors to the volume who defend the Church’s current positions on theological grounds and in the language of the designatedly “conservative” portion of the populace who perceive a “crisis in the family” because the majority of contemporary household arrangements no longer conform to the nuclear model that, as Tina Beattie points out, was an invention of the modern Western capitalist state (73). Lucetta Scaraffia in particular formulates the traditionalist stance by insisting that the women’s movement and the sexual revolution are social upheavals that have brought more pain than liberation to women.  She believes that a woman’s longing for self-realization through work is incompatible with “the joys of motherhood” (165), a modern dilemma when you consider that it was the Industrial Revolution that drove women out the home to find employment and it is the policies of our modern state that, in depriving women of paid sick or maternity leave, subsidized child care, and flexible work hours have made career and family financially and paradigmatically oppositional. Medieval women like Margery Kempe brewed ale, made cloth, sold their farm goods at market, and raised their babies, and nobody suggested they were inferior mothers for the time they devoted to bringing in household income.

She believes that a woman’s longing for self-realization through work is incompatible with “the joys of motherhood” (165), a modern dilemma when you consider that it was the Industrial Revolution that drove women out the home to find employment and it is the policies of our modern state that, in depriving women of paid sick or maternity leave, subsidized child care, and flexible work hours have made career and family financially and paradigmatically oppositional. Medieval women like Margery Kempe brewed ale, made cloth, sold their farm goods at market, and raised their babies, and nobody suggested they were inferior mothers for the time they devoted to bringing in household income.

Further supporting this notion that the family is in crisis, Scaraffia argues that a wife and mother is “irreplaceable” (current divorce statistics are bound to disagree) and that the “profound emotional gratification” that comes from motherhood cannot be found in “professional life” (165).

I would have to go back and read the Showings, but I don’t get the sense that Julian of Norwich felt anything less than “profound emotional gratification” from her work, or found her spiritual mentoring anything less than extremely maternal, and nobody pestered her to come out of her anchorite cell, find a man, and set herself to being a dutiful little wife. I won’t deny that centuries of women have indeed found profound emotional gratification from nurturing offspring, but the Cult of Domesticity that lies behind her rationalization of this family model and feminine disposition is a nineteenth-century invention that only ever worked for white, middle-class, heterosexual women. Furthermore, this exhortation toward mandatory mating and compulsory reproduction that the Church officially endorses has created centuries of pain for women for whom God’s plan is broader and more inventive.

It wouldn’t be a feminist review if I didn’t take issue with Scaraffia’s stance. But, more importantly, by a huge majority the contributors to this volume, beginning with Carolina del Río Mena, register a plea for a spiritual model that encourages women in “attaining full humanization” (27) on their own terms, in their own persons, and not solely in a capacity as mother and wife. Janette Gray makes a persuasive claim for acknowledging the personhood of the single woman—of which there are more these days, and more modern women spend more time being—and, moreover, for understanding celibacy as a respectable expression of human sexuality. As Patricia Stoat points out, “being single isn’t an unfortunate accident . . . [it] can be a vocation, an art form, a lifestyle, a way.” It’s different from marriage, true, but not “a lesser life . . . or a life less challenging or less complete” (128). Since, as Astrid Lobo Gajiwala notes, herding women into reproductive marriage has not infrequently led to “patriarchal control of their autonomy, sexuality and labor” (142), it might well be time to entertain some broader notions of the roles that women are allowed to play in this institution, in the social world, and in the domestic realm.

The book offers, in the end, far more than a reflection of women’s lived experiences and some pithy counseling to help the church come to “a wise and informed understanding of family life” (xxvii). It may have begun as a plea for “a more inclusive and pastorally responsive and responsible approach to families” (133) but what it offers is a call for “a cultural change, a change of mentality” (172) that rethinks the “theological anthropology” of current institutional belief into a more “useable tradition” (58) of Catholic moral theology, one that is more fully responsive to the truths of women’s lived experience and to the ongoing presence and influence of women in salvation history (170). It lays down an imperative for enrichment and enlargement, to hearten believers and summon doubtful to the faith by presenting “as broad a picture as possible of how God is acting in and with our reality” (173).

“Is it really imaginable that God can have devised a plan, or will endorse a way of being, that is consistently incapable of delivering justice to more than half the human beings in the world?” asks Sara Maitland (68-9). My answer is, probably not. This book, then, is a radical injunction for the leaders of the Church to think their way out of the social history that has hobbled its major tenets from the time of St. Paul and go back to the greatest of all Christian authorities, the divine Creator in whose image we are all made, for understanding of how each member of the Church body might “walk more closely in the footsteps of God” (192).

This is a wonderfully, thoughtfully crafted response, and I am sharing it. I enjoyed the accompanying artwork, too!