The answer, after reading Valerie Bowman’s latest and last installment of the Playful Brides series, is . . . yes. Yes, there can be, and there are, too many dukes in the world of genre historical romance. I am done, done, done with dukes, and this one has proved the tipping point.

Delilah Mountebank is surrounded by dukes. There’s Derek, husband to her best friend and fellow match-making whiz Lucy. There’s Thomas, her childhood friend who took on the burden of the dukedom at a young age and feels vaguely guilty for it. And then there’s the Duke of Branville, catch of the Season, whom Delilah boldly promises her mother she will wed, lest her mother promise her to Clarence Hilton, mere heir to an earl and therefore unmarriageable in this world where dukes and dukes alone matter.

What do dukes do, in this world where only dukes matter? They go to balls. They eat ices at Gunther’s. And they help their friends put on a play, Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, for a charity that will benefit an animal rescue society.

The premise of the Playful Brides series is one I can get behind fully: Each book is based (loosely) on a classic play. Here, though, there are lamentably few parallels to Shakespeare’s great and yet rather troubling comedy. (What’s to be done with Act V, for instance? Popular references leave out Act V as if it never happened, as it never happens here.) Nobody has to wear ass ears. There are no spirits promising mischief to the human world. There is no war in the fairy realm, no argument over a stolen child that has disrupted weather systems, no conquering Duke of Athens who has brought the great Queen of the Amazons into the subjugation of heterosexual marriage, and no set of rude mechanicals hoping to elevate themselves, or earn a few pieces of coin, by bowdlerizing classical mythology for the entertainment of their social superiors. There are no intriguing monologues on the nature of art, no impassioned masochism on the part of the spurned woman, and no fleeting yet hugely poignant references to a shared idyllic girlhood now violated and made impossible by the competition for a rich mate and therefore a financially and socially secure life.

There is, in fact, no evocation whatsoever of Shakespeare’s play save for the “love” potion which Delilah obtains from an obscure shop run (of course) by an enigmatic Roma, and which she intends to dribble on Branville’s eyes not so she may amuse herself at his expense, as Oberon intends to manipulate and embarrass Titania, but so Delilah might ensure Branville’s romantic attentions and thus demonstrate to her mother, who has never valued or appreciated or indeed been at all very nice to her, that Delilah is not the ridiculous failure her mother believes her to be.

Never mind that the scene that introduces us to Delilah shows her shredding her dress and debasing herself by chasing through her mother’s elegant townhouse after . . . a squirrel. The squirrel pursuit is in fact the sole element of this book–plot, character, subject, and theme–that I haven’t seen anywhere else. Cheers for the squirrel!

The book jacket makes much of the love potion because it is the only thing that actually *happens* in the book. The entirety of Acts I, II, and III are composed of people standing around, either in a ball room or at play rehearsal, discussing who ought to be matched up with whom (with breathless disregard for the actual feelings of those involved). There is no world in this world but marriage and leisure, the sole pursuits of the moneyed class.

Act IV offers the slightest veer into real emotional weight when Delilah realizes she dripped the precious potion on the eyes of Thomas–the wrong duke!–and has tricked her best friend into thinking he’s passionately in love with her. Suddenly, from nowhere, Delilah sprouts the barest hint of an adult conscience and sense of morality, and realizes she’s played an awful trick. Moreover, she suddenly grows up so much in her character (and her aspirations) that she *can’t* lure her friend into a lifelong dupe and sham. She just can’t!

The twist, of course, is that Thomas has loved her all along, and has (completely unlike the Duke of Athens, or Demetrius, or Lysander, or even Oberon) been patiently waiting for the moment Delilah will decide she wants a boyfriend–I mean, a duke of her own–at which point he will swoop in and offer her a lifetime of wealth, financial security, social stability, and emotional support. (THAT, after all, is the chief fantasy these novels deliver–that, and fantastic, transcendent orgasms, every time.) Thomas is a Bottom–but not in the sense that he is bossy and a bit dense, and a social aspirant, and always pretending to know more than he does. Thomas is Bottom just waiting for Titania to open her eyes and exclaim, “I love thee!” There’s a lovely absurdity in the idea that the subject of the love potion must persuade the potion bestower of the depth and validity of his passion–not the efficacy of the herb– and these are the best chapters of the book.

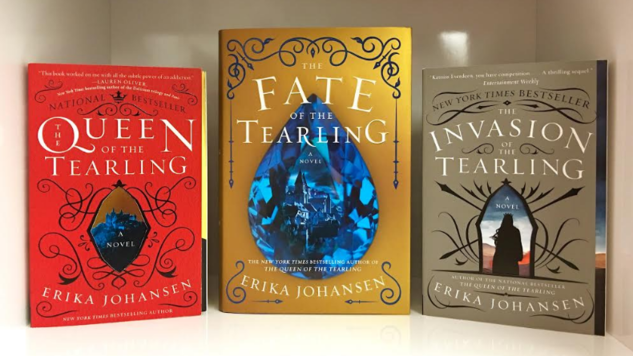

Those who have followed the Playful Brides series will appreciate the scenes that are jam-packed with previous pairs merely to get them all on stage; NO OTHER DUKE is less a developed book than a “where are they now?” featurette for the boxed set release. Those who have read the stories of the last two Playful pairs–Mark and Nicole Grimaldi, spymasters extraordinaire, and Regina and Daffin, who fall in love between kidnappings and attacks–will notice a distinct change in tone. Whether that’s an improvement or not depends entirely on the reader’s taste–and their tolerance for dukes.

P.S. I wasn’t being completely fair in this assessment. There is one real reference to the Shakespeare play. A character recites Puck’s speech in the Epilogue. As an apologia from the author it is playful and fitting, but I couldn’t help but recall how powerfully that play affects me still, how it yields something rich and deep and strange and newly puzzling with every reading–and the epilogue left me with the regretful acknowledgement of how very, very far Shakespeare is from this book. So it goes.