This book is for every woman who’s had a C-section. It’s for every woman who is pregnant and might have a C-section or women who have been told they won’t be able to give birth vaginally but want to become pregnant. It’s for every woman who has given birth vaginally, so you know what was going on with your sisters in the maternity ward. This book is for every person associated with the birth industry in any fashion, from doula to OB. It’s for every mother who ever went through the process of having a small being expelled from your body and put in your arms, because–surprise!–every birth mother can relate to this strange and jarring and wringingly painful and profoundly moving experience no matter how that child ended up on her.

There’s nothing different or odd or wrong about women who give birth via C-section. That’s the big, shocking revelation of this book. These women didn’t pursue some selfish whim to make birth “convenient” for them. (When is major surgery on vital organs ever convenient?) Those who plan C-sections do so to minimize risks in a “natural” process that can easily–and often does–go horribly, unpredictably wrong. Some of us were urged to plan a C-section by others who understood the risks better than we did. More of us planned on doing things the old-fashioned way and found in the birthing bed that something went horribly, unpredictably wrong and a C-section probably saved the lives of us and our babies (except in the awful, painful situations where it doesn’t).

There is such an established, vocal, and persistently expressed adulation for vaginal birth that women who don’t get to participate are left feeling left out of the club, denied their Badge of Honor for Enduring an Incredibly Painful Experience. We are made, often, to feel shamed or incomplete, like we didn’t do something “right.” Like there was something “unnatural” about our delivery process that left an imprint on our babies, because we didn’t give these precious beings their best possible launch into the world. In addition to the surgery like slices us open like a hog, and the additional physical trauma from which we have to heal, C-section moms are given this extra burden of guilt, shame, loss, or not-enoughness to carry around along with their newborn. And you’re not supposed to talk about it. If you deliver vaginally, you get to brag about the hours of labor as a sign of your endurance and athleticism and supermomness. If you’re a C-section mom, you’re expected to just get over it.

This silence around the C-section is what led editors Amanda Fields and Rachel Moritz to design and develop the powerful, urgently beautiful collection My Caesarean: Twenty-One Mothers on the C-Section Experience and After, out now from The Experiment. In it, women writers–in loud, gorgeous voices and full technicolor detail–break the barriers of silence and shame. They tell their birth stories in their vivid and individual specificity, each unique and each so powerfully similar. They tell us, in a musical and poetic and painful and compelling chorus, to see and acknowledge the C-section experience, its particular dangers, its attendant losses and fears. They challenge us to understand why a woman might choose this means of extraction, or why her choice might be taken away. They demand that we listen, that we understand, and that we change the conversation about childbirth to eliminate the blind spots and silence and the ways the experiences of some are used to invalidate the experiences of others.

Because what’s never talked about in the bookshelves full of gestation literature–or at least wasn’t when I was reading them–and isn’t discussed in birthing classes, either–at least, not the one I took–is how very many ways there are that a pregnancy and birth might go horribly wrong. “We fetishize the birth experience,” Jacinda Townsend writes, and that ideal of the glowing 9-month gestation leading to a handful of hours of painful labor and exultant delivery with instant bonding and breastfeeding is treated as the norm. “I wanted the conditions in which my daughter entered the world to be at their most optimal and pure (meaning, not medically invasive),” SooJin Pate confesses.

But in fact, there are any number of complicating factors. Previous abdominal surgeries might compromise the uterine wall and the ability to labor in ideal fashion, as Judy Batalion and Susan Hoffman describe. Other fairly known dangers include pre-eclampsia, placenta previa or placental abruption, low fluid, the umbilical cord wrapped neatly around baby’s neck (“‘He was all tangled up like a Christmas ornament,’ the OB said while the intern sewed me back up. I lay with my arms straight out, a horizontal Jesus, shivering from the anesthesia,” Alicia Jo Rabins writes.) There’s the quite common “failure to progress,” which as Sara Bates candidly points out, is “quite the mindf**k for a Type-A who’d devoted the past thirty weeks to controlled breathing, deep squats, organic coconut oil massage, and red raspberry leaf tea . . . Pay no attention to that failure behind the blue curtain!” And then there are the rare and little-known but desperately serious conditions like HELLP syndrome, which Daniela Montoya-Barthelemy writes about with matter-of-fact intensity.

There are other reasons a surgical birth might be decided on in the moment, and none of them are the mother’s “fault,” unless you want to blame us for uncooperative, non-ideal bodies. The cervix doesn’t dilate (“My cervix was a walnut shell, stinking and impenetrable,” writes Amanda Fields). The baby is breech. (“Bottom first tucked in my pelvis,” writes Mary Pan. “This wasn’t supposed to happen.”) Sometimes the canal architecture isn’t the norm–this happened to Jen Fitzgerald and Cameron Dezen Hammon–and the baby would never have emerged in the customary fashion. Robin Schoenthaler‘s essay “Wounds” tell us exactly what happens when a caesarean isn’t done on time, when “a doctor tiptoes around the ‘caesarean’ word until there is no chance” the baby can survive. (Prepare to shed tears reading this one.)

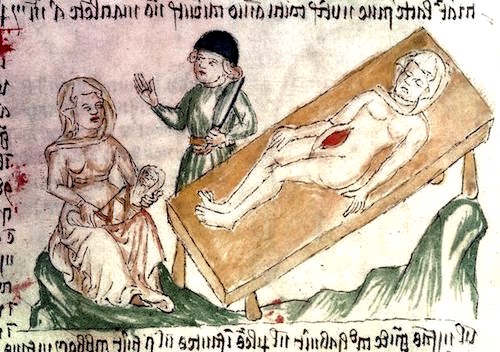

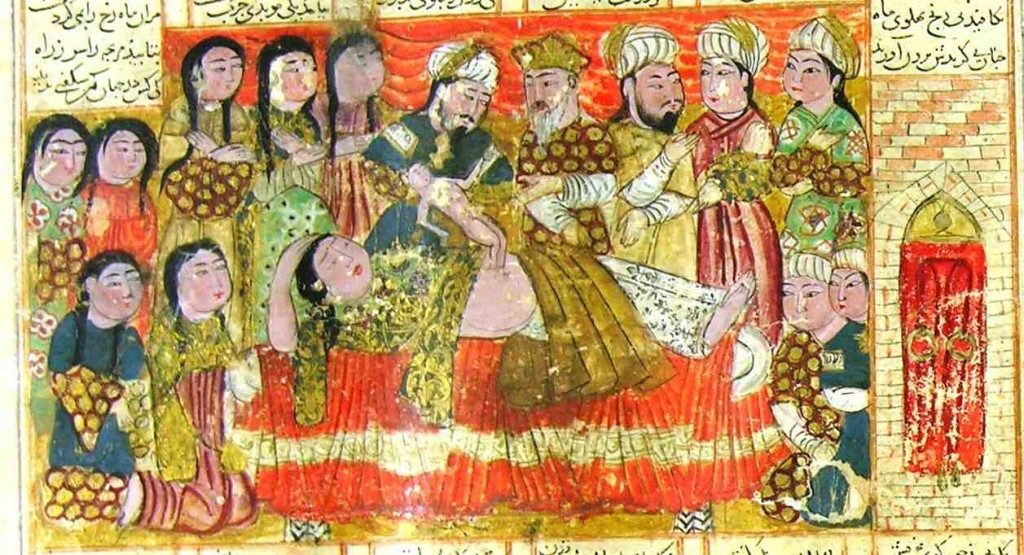

Elizabeth Noll, giving a history in “The Emperor’s Cut,” reminds us that this perception that the C-section rate is “excessive” leads to at least 3 million cases a year where a C-section could have saved a mother’s life, but wasn’t performed. As Tyrese L. Coleman dares to speak it out loud: the silent condemnation that women who plan, who prefer C-sections, are “selfish.” “Forgive me,” she writes acidly, “for not wanting to associate my children with the continued violation of my body.”

More than just articulating the many reasons women may give birth via C-section, this collection is remarkable for the way it describes this shared experience in individual, incredibly powerful ways. Aimee Nezhukumatathil writes with hallucinogenic lyricism and Catherine Newman with quick punchy prose about the disorienting experience of birth, while Nicole Cooley uses the story of Rapunzel to explore her fears during pregnancy and after that her daughter would be bewitched away. Rachel Moritz describes with precision the daze of pain and thick not-quite-numbness that follows the sleepless hours of labor then surgery then drugs.

Several of the essays deal, eloquently, with how we come to terms with our experience, after. LaToya Jordan uses the image of the Zig Zag Mother, like the magician’s assistant put into a box and cut apart. Lisa Solod wrote a letter to the OB who, in labor, was too far away for comfort: “Maybe it was because my treatment had been so brutal, so out-of-body in so many ways, that I needed someone to understand just how hard I had tried.” And Misty Urban (that’s me, dear reader!) thinks about how long and dark the recovery process can be when we’re not told what to expect–for instance, that women who deliver via C-section are at a higher risk for perinatal mood disorder (PND), including depression, anxiety, or just acute, chronic insomnia, which is what happened to yours truly.

These 21 women come together to paint a fuller, truer picture of what happens behind and around that blue surgical curtain. Even Maggie Smith, invited to contribute a foreword, was moved enough by the collection to add her own birth story. C-section is birth and should be celebrated as such. The stories told here will evoke laughter, breathlessness, tears, ghost pains, and howls of recognition. They will make your scar itch and they will make you want to rub your nose in your child’s hair, remembering that transformative moment when you first met face-to-face. This brave, brilliant, and astoundingly well-written collection smashes the walls of silence and shame and lets C-section survivors celebrate each other as fellow mothers, as sisters on the surgical table, as patients who went under the knife and came out changed.

Yes, the maternal mortality rate in this country is troublingly high (and, outrageously, immorally, higher for Black and Native American women than others). Yes, there are very real and urgent problems that need to be addressed and resolved about “medicalized” birth and the kinds and pacing of interventions performed. But these conversations need to progress with some sensitivity and awareness of that fact that, rather than being an unfortunate freak accident we shouldn’t talk about (like pooping on the delivery table), a full 1/3 of births in the US are C-section deliveries. Look around you. One of those three annoying kids running around the playground, the supermarket, the restaurant might not be here without that intervention. Those moms look and act like real moms. Their kids develop and learn and tantrum and question and irritate you just like real kids. Let’s give everybody who comes out of delivery a gold star for participation, okay?

That means that we won’t resent or judge you, vag-delivery champions. We’ll let you in the clubhouse. We won’t shame or guilt or tease you for your easy, glistening, athletic birth. We’re all moms here.

This is a necessary book.

Thank you for this brilliant review, Misty!

Rachel, thank you for this BOOK!

BTW I shared this review on FB, and it sparked a really great convo among people who are very supportive. Looking forward to the book!

SO glad to hear that! Thanks for continuing the conversation – that’s one of the big aims of this book.