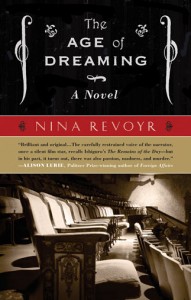

Nina Revoyr is the author of five novels: The Necessary Hunger (1997), Southland (2003), The Age of Dreaming (2008), Wingshooters (2011), and most recently The Lost Canyon (2015). She is also executive vice-president and COO of Children’s Institute, Inc., a non-profit serving children affected by violence and poverty in Los Angeles. Here, she talks with poet Lauren K. Alleyne about badass women, committing to a novel, and the power of paying attention.

LKA: Tell me a little bit about your journey to writing. How and when did you know you wanted to be a writer?

NR: [laughing] Do I want to be a writer? Do I really?

But seriously. Writing was a natural evolution from reading for me as for many people. I read a lot when I was younger. I was born in Japan, and my mom’s Japanese. I was the one mixed-race kid in my school there. Then I moved to rural Wisconsin, where I was the one kid of color in that school there, so everywhere I was I felt out of place. I read books to keep myself company and to be part of a different world than the one I actually lived in. I started writing soon after that, and in some ways that impulse is still there. My everyday life is much happier, much more satisfying than it was when I was a kid, but writing is still a way for me to create an alternative world that is a bit more interesting or different than the real one.

LKA: Who were some foundational writers for you?

NR: You know, I wasn’t necessarily a sophisticated reader. I remember a lot of the then-important YA books, Robert Cormier, Lois Duncan. I also loved The Chronicles of Narnia. And there was something about that, maybe—I’m just now making this connection—that had something to do with being an immigrant, with the idea of leaving a comfortable world, going through a doorway and entering a completely new one where you didn’t understand any of the rules, any of the landscape, any of the people, and had to negotiate through that and find a place there. So maybe that’s part of why that series resonated for me. I also read and loved The Lord of the Rings, maybe again because of that whole idea of being part of a different world. It wasn’t really until college, and then beyond college, that I got exposed to the writers that really influenced me as a writer.

LKA: And who are some of those?

NR: Certainly people like Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Louise Erdrich, all of whom I loved and read at key points. I love Salman Rushdie. Those were people who really spoke to being a person of color, and to writing ideas of family history, identity, immigration, you know, finding your way within America as someone who was other. And then I was also drawn perhaps counter-intuitively to these folks who wrote a lot about the land, and folks who are more associated with rural white reality, which of course I was also exposed to. So I love Norman Maclean. I love Wendell Berry. And then there were poets! I don’t want to leave out the poets. I love, love, love, Emily Dickinson. I’ve been to Dickinson’s house twice. I love Elizabeth Bishop. I love Gwendolyn Brooks. Love her.

But the writer who has been the single biggest influence for me has been James Baldwin. And the only thing of his that I read in college was the story “Sonny’s Blues,” which to this day may be my single favorite short story in the world. I didn’t read the rest of his fiction and non-fiction and plays until my early twenties, after college. But that was like finding an ancestor for me. I just felt such an affinity on so many levels around race, around sexuality, around the way that he engaged with the world as a writer and intellectual, and his language is so amazing. He still blows me away! I would think of how he handled things or how he characterized things, and I learned from his brilliance, and I learned from his errors. He’s probably the single person I regret not meeting in my life. He’s been a huge influence on me for sure.

LKA: So you write novels, but do you ever experiment with the short story or other genres? Why or why not?

NR: I experimented with poetry, but it’s better for everybody that I stopped. I was a terrible, overwrought, emotional, very sincere poet. And it was just sad for everybody involved. [laughs] It’s true!

NR: I experimented with poetry, but it’s better for everybody that I stopped. I was a terrible, overwrought, emotional, very sincere poet. And it was just sad for everybody involved. [laughs] It’s true!

I did write some stories in college, but they weren’t any good, and the ones that were decent or had some kernel of quality ultimately became the seeds of my novels. I think I just need the space and the expansiveness of the novel to really spread my wings and explore all the things I want to explore, and include different people. The short story is kind of like an affair, and a novel is like a marriage. And I’m the marrying kind!

LKA: That’s awesome. And so what’s the most challenging part of the marriage? Of writing these novels?

NR: It is sustaining the sense of urgency and magic and intrigue. Which many people (though certainly not me) would say about marriage as well. But for me, a book takes me three or four years to write, and so I have to have a question or problem that’s compelling enough to chew on for that long for me to keep wanting to go back to the desk time after time after time and keep working on it. And so between each novel that reaches publication, I have a failed novel. I wouldn’t say there’s a one to one ratio, but I have several really significant failed projects, where, I wrote a hundred or two or three hundred pages, and it just wasn’t alive enough. It just wasn’t urgent enough.

LKA: How do you know when to break up with a project? I mean, three hundred pages? At that point, aren’t you like “we are so staying together!”?

NR: No! It’s more like “I’m sorry, the feeling just wasn’t there!”

I had this happen very significantly with this book that just came out, Lost Canyon. I’d been working on another novel for two years. I had over two hundred pages. I thought it was really immediate and important, and there were all these things that I wanted to tackle, and all this meaning and significance. But every day I sat down, and it felt like work. It felt like I was forcing it, it felt like an obligation, as opposed to a desire. And literally, I was hiking in the mountains at 10 thousand feet, and I felt . . . wow, why am I not trying to capture this sense of excitement? And so I went back to the book I was working on, and I said, “Sorry, it’s time to break up. I gotta go pursue this thing that’s really turning me on!” And that became Lost Canyon.

I had this happen very significantly with this book that just came out, Lost Canyon. I’d been working on another novel for two years. I had over two hundred pages. I thought it was really immediate and important, and there were all these things that I wanted to tackle, and all this meaning and significance. But every day I sat down, and it felt like work. It felt like I was forcing it, it felt like an obligation, as opposed to a desire. And literally, I was hiking in the mountains at 10 thousand feet, and I felt . . . wow, why am I not trying to capture this sense of excitement? And so I went back to the book I was working on, and I said, “Sorry, it’s time to break up. I gotta go pursue this thing that’s really turning me on!” And that became Lost Canyon.

On a more serious note, the whole thing about knowing when to quit is that I don’t believe in writers block for me. If I’m having that much trouble getting on with a story, or that much trouble figuring out what comes next in a story, or even just sitting down to do it, then there’s some larger problem at play. And so I have learned in my career to listen to that. That if I’m resistant, if I’m forcing it that much, it probably means that there’s some kind of intrinsic element missing, and in this last case when I threw out the other book, and sat down to write this one, it came much more easily, and it was far easier from start to finish.

LKA: What’s the most fun part of the writing process for you?

NR: I like the stage when you feel like you’ve really got something, you’re really on to something, but you still have a lot to figure out; that’s part of the fun too, the exploration, the not knowing what the next corner will bring. And by the time I’m reaching the end and it’s all starting to come together, and the pieces start to fall into place, that starts to feel really wonderful, too. But then I always feel a great sense of loss when it’s done. The real joy for me—and I think this is a common experience—the real joy for me is the process of the work. Everything else that happens after that is gravy. It’s wonderful, but it’s the satisfaction of doing the work, and figuring these things out, and making these people and stories come to life that’s the real happiness for me.

LKA: You’ve written five books: does it get any easier?

NR: It ebbs and flows. It comes and goes. The book before this one, Wingshooters, which is a shorter book, took much longer to write. That’s an example of something that started as a short story in college, and then I’d put it aside, and a few years later, I wrote a little bit more, and then a few years later, I wrote a little bit more, but I didn’t know what the story was. I knew who the characters were, but I didn’t know what the story was. Once I figured that out, then it came fairly quickly, but from start to finish, that was 20 years. So once I got going, it was easy, but the getting going took a decade and a half. Several of the books have been very hard. This last one came very easily. It was not since my first book that I have had that much fun. I don’t expect it to be that easy again. If you’re a writer, you get one or two of those in your life, where it’s just a joy, and where it flows pretty well, but . . . I’ll take it.

NR: It ebbs and flows. It comes and goes. The book before this one, Wingshooters, which is a shorter book, took much longer to write. That’s an example of something that started as a short story in college, and then I’d put it aside, and a few years later, I wrote a little bit more, and then a few years later, I wrote a little bit more, but I didn’t know what the story was. I knew who the characters were, but I didn’t know what the story was. Once I figured that out, then it came fairly quickly, but from start to finish, that was 20 years. So once I got going, it was easy, but the getting going took a decade and a half. Several of the books have been very hard. This last one came very easily. It was not since my first book that I have had that much fun. I don’t expect it to be that easy again. If you’re a writer, you get one or two of those in your life, where it’s just a joy, and where it flows pretty well, but . . . I’ll take it.

LKA: So you mentioned “bringing people to life” in your writing, and one of the things I certainly notice is the diversity of your characters; they’re sexually, racially and economically diverse. I’m interested in the choices and challenges involved in shaping that kind of inclusivity in a narrative.

NR: In terms of the choices, it would be a choice not to include such diversity. You know what I mean? It would be a conscious decision to exclude, because my life—both my professional life and my personal life— includes a very diverse set of people. And it’s that diversity, it’s that reality, particularly here in Los Angeles, I’m trying to reflect in my fiction. To only write about someone who was the exact representation of me, which is to say, Japanese and Polish with a French last name, who lived in Japan and then in rural Wisconsin then moved to urban and largely black and Latino neighborhoods in LA, that would be pretty narrow! I mean how many characters could I write that were exactly like me? That would get old pretty fast.

It’s important to me to actually reflect the world as I experience it, with the kind of complexity and diversity that I know because I think it’s still not represented enough in fiction. I still think we don’t see enough people of color, and we almost never see the possibility of the ways that those people of color, communities of color might interact with each other as well. And in that’s the same in terms of sexual orientation and class.

Just to give you a sense, in my work life, on Friday, I started out in Watts with a group of people that included some pretty notorious former gang leaders, with people who are living in incredible poverty, and I was helping to facilitate a meeting with a public official where they were airing some of their concerns. And then I went right from that to a meeting in a very wealthy area in Los Angeles, where I was dealing with some very rich people, to talk about how funding might be secured to help social services within Los Angeles. So in four hours, I went from extreme poverty to extreme wealth and everything in between.

That’s the world as I know it. That’s the world that I want to make visible within the fiction. It’s really important to me to help make visible people and experiences that are not visible, and that are not commonly seen in fiction. And the same with places, you know, I want to write about areas of the city that are not usually written about in a loving way. I think that’s so crucial and so important.

That’s the choice of why. The challenges are also multiple, because it’s very hard to try and imagine what’s at stake for such different groups of people. And because I choose not to only write from the perspective of characters that directly reflect me, that means having to take a leap of imagination, whether it’s across gender or across race or across class, and try to imagine the world from someone else’s point of view. And that’s not easy. It takes a humility, it takes an openness, it takes the ability to observe, it takes an understanding that you don’t have the answers, and it takes the ability to ask sometimes—and to be corrected. So it’s very challenging to try to get these things right, but I can’t imagine not including this variety of people within my books, because that’s the world as I know it.

LKA: It seems to me that you’re saying it’s work, but it’s important work. And I want to know more about your experience doing that work. In Lost Canyon, for example, you go between four voices. Did your head hurt? Did you write each of them in the story order? Did you write it character by character? As a reader, I felt really inside of each of the characters, and very aware that I had moved into a different mental embodiment, so to speak. How did you do that?

NR: It was so much FUN! I have to say that it was also a relief. It is also very difficult to sustain one singular point of view or one voice, for 300 pages, as I did in the previous book. Three of my five books have been in first person narrative, and it’s very hard to sustain the same voice for that long, and so in some ways, this was almost easier because I got to go from character to character. And it was really fun.

For example, Oscar’s got a bit more attitude; he’s a little bit more sardonic. Gwen is not fully confident, more doubtful about herself, but becomes fierce over the course of the story, and shows her strength.

LKA: Gwen is a badass.

NR: She’s a total badass! But she needs to go through the story to realize what a badass she is. And Todd is kind of clueless, but he receives a clue through the course of the story. But what was fun about that set up was that I got to show through each of those characters’ eyes, not only their perceptions, but their misconceptions about each other, about what they were experiencing. And then throwing them together was a chance to see how they were going to affect each other, and what impact it would have on all of them to be in a situation of danger, where they were going to have to learn to get through their differences in order to survive.

And it’s interesting, because each of these characters was a challenge in a particular way. With Todd, it was really trying to understand—for me as a writer, to un-see, or to un-understand my view of the world, and to write a white character who didn’t perceive the racial dynamic surrounding him. Of course, he redeems himself, but that’s where he starts out. In Oscar’s section, it was that I’ve never had a really significant Latino character in my books before this book, and so that was a whole different challenge, and also a little daunting. With Gwen, the biggest challenge was not really that she was black, but that she was a femme. Let’s just say I’m referred to as ‘sir’ more often than I am referred to as ‘ma’am’, so trying to understand the point of view of a woman who is more traditionally feminine and probably heterosexual was the challenge. How is she going to interact with these straight men? How does she see herself? So, with each of these characters, there was a particular challenge. But that’s part of what I want to do.

And also it was fun to have the one character who directly reflected my own racial mix, to not have a voice. Because I’m also playing with that idea of who we assume is the stand in for the author. It was just a lot of fun.

LKA: Backing up to something you said earlier, you said you need to “allow yourself to be corrected”, and I’m curious about your checks and balances. How do you catch a misstep? Where does the correction come from? Tell me about that process.

NR: Those are tricky dynamics, too, because you need to have really trusted readers. If I’m writing from a guy’s perspective, I’ll just say to a male friend, look, as a dude, how would you react to this situation? With Oscar, I definitely leaned on [my wife], Felicia, who is Chicana, particularly around some of the family dynamics. And even with Gwen I leaned on her a little bit. There’s a scene right before they go on the trip when Gwen wonders whether to take her makeup. That’s the last thing in the world that would occur to me, so I would ask her “Felicia, would Gwen take her makeup? How would she feel about this or that? How would she read that?”

Sometimes it is self-correcting, or being extra aware. One thing that I really became mindful of was the character’s bodies, because so much of this book is about the comfort of oneself in one’s body. And of course the group is led by Tracy, who’s this fitness person. There was a moment when that whole thing blew up about that white woman who was in a yoga class, and she was looking at a black woman in her yoga class, and expressing pity because the black woman didn’t fit her definition of beauty, which in part meant having a particular body type. That was so offensive on so many levels. So it became very important to me to make very clear that Gwen’s gaining power over her body is not about being skinny. Tracy, who’s Asian, is not described as thin; she’s described as strong. And Gwen’s comfort and increasing acceptance of her physical being is not about having a certain body type, it’s about being strong, and at ease with herself. So that was a moment of heightened awareness, for example.

But also I just give my manuscript to friends to read, and I have got friends who will let me hear it if I get anything wrong, and that’s what you need.

LKA: Have you found that your own identity as mixed race, as a minority, and a writer of color affected your experience in publishing and writing?

NR: Yes, of course. But I also think that there are so many different ways in which I’m “other”: I’m gay; I’m an immigrant; I’m mixed race. But I also write about mixed groups of color, so it’s almost like there’s no easy box to put me in. I am taught in Asian American Literature classes, and that’s terrific, but I also do think that some more traditional Asian American fiction readers might have a harder time knowing what to make of the fact that I also write about African American and Latino realities. There was a time, of course, when being a lesbian just flat out meant that I did not have access to certain audiences or venues, but then when you look even at that part, mainstream LGBT communities have not always really been inclusive or understanding of the challenges of people of color. I kind of hit so many boxes, but don’t completely belong into any one, and I think that has been a challenge.

But that being said, I have a wonderful publisher that doesn’t push me in one direction or another, and allows my writing and me, and all of our complexity.

LKA: You also work full time in the non-profit world. Tell me how that affects your work as a writer.

NR: I love my work. For a number of reasons. I love the work itself. I actually get to have very direct and tangible impact on people, on children, on children of color, and on disadvantaged communities. To get to see the tangible effects of that— to see kids getting better education; to see kids who have faced trauma get help so that they can recover; to help kids maybe make different choices, you know, not enter gangs, and to move in a more productive way; to help parents— all feels valuable, and I enjoy that.

I think that it’s also actually been a balance. For years I thought these two things don’t go together, that I’m fitting my writing around my job, and they’re so separate, but what I realized is that separation in itself was healthy for me, because that meant for 8-10 hours a day I get to not think about my writing. For me that’s actually good. I get to immerse myself in something else; I get out of my own head. I mean how many of us writers get lost in our own heads sometimes? And so when I actually return to my writing it’s a joy. It’s a relief. It’s a respite, and it’s like a playground. It’s getting to play. And because my writing is so completely divorced from my job, no one’s expecting anything from me. You know, I have no one watching over my work; no one’s wanting to see it for tenure purposes. That does give me a freedom that I think is very healthy. The biggest challenge, of course, is time. But I do the best I can.

LKA: How does teaching fit into all of this?

NR: Actually I haven’t taught in a while. I think the last time was a year and a half ago—winter of 2013. I had to scale back, because it would kill me to take on any more. And I miss it. I love interacting with students, but I try to get that interaction in other ways. Just this week, Southland was a common book selection for a college, so I got to spend two days interacting with these amazing college kids. That charged me up. And I’m going to do another event with a group of students this weekend, so that’s how I get my fix of interacting with students. But yes, I miss it very much. I love teaching.

NR: Actually I haven’t taught in a while. I think the last time was a year and a half ago—winter of 2013. I had to scale back, because it would kill me to take on any more. And I miss it. I love interacting with students, but I try to get that interaction in other ways. Just this week, Southland was a common book selection for a college, so I got to spend two days interacting with these amazing college kids. That charged me up. And I’m going to do another event with a group of students this weekend, so that’s how I get my fix of interacting with students. But yes, I miss it very much. I love teaching.

LKA: Do you consider yourself a feminist? And if so, tell me what that term means to you and how you apply it in your writing and writing life.

NR: Yes. Of course. And for me, it’s not a term that is so controversial and so contested. What it means to me simply is someone who cares about, and is concerned for, and advocates for, women to have the same opportunities and the same respect as men or as everyone else. But I do see being a feminist and caring about women’s rights as part of a larger landscape about caring about the rights of communities of color, caring about LGBT rights, about caring for immigrants, etc. And I don’t mean that to qualify it, I just mean that for me, it’s never been a term that had a negative connotation, because it just so obviously about wanting the best for women.

And thinking about how it plays out in my work, my writing, it’s just that I really try to create some, as you say, ‘kick ass’ women. In this last book, Tracy starts out as the seemingly the strongest of all four of them, but it’s really Gwen who has the transformation. In each of my books, there’s at least one really strong woman and often more. I think of Hanako in The Age of Dreaming, the Japanese silent film actress who wound up being much stronger, and much more ethical than any of the men. In each of the books there’s always strong women, sometimes in unexpected situations. That’s how it plays out.

LKA: So your partner, Felicia Luna Lemus, is also a fiction winter and a novelist (and a badass woman in her own right!). What’s it like having two novelists in one space? Does that affect the writing or the relationship?

NR: Well, for starters it means that when you live with another novelist, you can’t get away with “not now honey, I’m writing.” When you’re with a non-writer, what you do is mysterious; if you say “don’t talk to me now, I’m creating,” that works. There’s no BS-ing here, though.

NR: Well, for starters it means that when you live with another novelist, you can’t get away with “not now honey, I’m writing.” When you’re with a non-writer, what you do is mysterious; if you say “don’t talk to me now, I’m creating,” that works. There’s no BS-ing here, though.

But actually it’s wonderful. We’re very different about how we share and don’t share our work. I didn’t share any of this book until I had a complete first draft, but then she was the first reader. She’s just a fantastic reader and editor for me, and this comes, I think, from her being such a great teacher, too. I just trust her take, and to have someone who is that invested your work, but also who loves you, and also has the ability and the guts and honesty to be like, honey you’re getting this all wrong, or you’re getting this right: it’s amazing. The funny thing is that our tastes are so different, so we get into some pretty intense debates and discussions about other books, but we’re huge fans of each other, and I think that’s been wonderful because we each understand what the other person is trying to do.

LKA: Are you working on something new?

NR: I am. Although I have not really looked at it in the few months since my book came out. Once everything is over, which is another two or three weeks in terms of events for this book, then I’m going to dive back in. I’m excited. Because that, as we’ve already established, is the really fun part.

LKA: As a woman, as a writer, as someone who has a deep relationship to language, what words of wisdom do you have to share with our readers?

NR: Well, I think some of it would be the conventional things that others have said: to read everything, expose yourself to lots of different kinds of writing, and to actually sit down and write.

But I think it’s so important for us as writers to really be present where we are, and to really be open to experience. And so it’s about letting yourself do things as a person that might seem whimsical, that might seem impractical, but to do them just for the heck of it. When I was speaking to the kids this week at Loyola Marymount University, I told them the story of Steve Jobs taking a calligraphy class in college, and how it had no practical application—he was just drawn to the beauty and the simplicity, and the story of it. It had no bearing on his life until ten years later when he was designing the first Macintosh, and then suddenly the same lessons of simplicity and beauty came back to him. The things that seem the most impractical or indulgent at the time might actually come back and inspire or feed into something later.

But also this idea of just being present, and really noticing— whether it is being completely in your body, or really noticing the world around you, whether you’re in the city of the country. Most of the details and descriptions in Lost Canyon were really things where I just looked at something and thought ‘wow, this looks like that’ or ‘this reminds me of this’. It’s just paying attention. It’s the same with people. If you are a writer, whether you’re a poet or a fiction writer or a non-fiction writer, ultimately you’re dealing in people. And in order to characterize and represent people artistically, you’ve got to really notice them—whether it’s physical things, or what someone acts like when they’re nervous or unhappy, or the way that they sit, or what they do with their feet when they’re sitting, or what you consider sexy in a person— all of that stuff becomes the fodder for the details that go into your writing. It’s just a very basic thing of opening yourself to experience and really being present. Those would be my bits of advice.