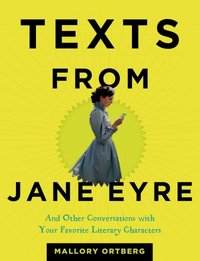

It’s as funny as it ought to be: eaves-dropping on text conversations between your favorite literary characters, complete with acronyms, emoticons, irregular caps, and characteristic grammatical errors. (See the original texts from Jane Eyre on The Hairpin, if you’re intrigued but not ready to commit.) I started with chuckling at Medea, passively-aggressively badgering her lover’s new girlfriend. I laughed out loud in the coffee shop when Gilgamesh asked Ishtar “how about all your other boyfriends / still horribly dead / or turned into wolves?” (7). Achilles sulking in his tent had me laughing till I cried; by the time Glaucon was responding to Plato’s speculations about “The Cave” with “WHAT FOUL SPIRIT WOULD CHAIN HUMAN BEINGS UNDER THE EARTH LIKE HADES” I was nearly hysterical, laughing and crying together, and it was only page 13. You get the gist, and ancient texts nor the classics are not the limit; the literary creations (or personae) of Chaucer, Shakespeare, the Romantic poets, Poe, Dickens, and Virginia Woolf give way to Sweet Valley High, Fight Club, the Babysitter’s Club, Ayn Rand, and Harry Potter. Any one of these should have already sent you to your favorite local independent bookstore to order your copy of this book now.

The conceit is cleverer than I expected, and Ortberg uses it in different ways. If all the entries were on the model of Scarlett drunk-texting Ashley or asking Mammy to bring her chocolate despite being in bed with typhoid fever, Holmes informing Watson he’s going on a cocaine bender, or Gatsby’s Daisy begging Nick to come pick her up in the Valley of Ashes, at midnight, “nearrrrr the road / but not on it exactly” (153), the chuckles would wear quickly, and the book only enjoyable in short, select bursts. But Ortberg mixes it up, sometimes extending the story by introducing other characters, as in the anonymous “friend” informing Winterbourne about Daisy Miller: “Daisy diiiied . . . she went for a walk outside / with an Italian / at night / under the MOON . . . so / you know / obviously / that killed her” (165-6). Or she gives voice to hidden sides of a character, as in the Rebecca de Winter’s housekeeper informing her, “you’re using the wrong fork you know” (210).

And sometimes the exchanges play on the reputation of a literary great, like Byron moaning that he wants to have sex with the rain, “I want to have a threesome with the moon and jealousy,” to which the anonymous friends can only reply, “right / Yeah” (64). The same friend soothes a poeticizing Emily Dickinson, responding to “Toads can die of light you know” with “I believe you / Kill them right up” (57), while William Carlos Williams’ exhausted wife responds to his request to go back to the store to buy plums and because “i have eaten the little red wheelbarrow / that was in the icebox” (219). But the most hilarious are those that take a playful peek at the moment of literary creation, like Keats: “oh my god / oh my god . . . THIS URN . . . THIS GRECIAN URN” (66) or Coleridge, speculating on the imagery of “Kubla Khan,” interrupted by a knock at the door (43). Have you bought this book yet? If absolutely nothing else, it’s a crash course in Western literature from its beginnings to The Hunger Games. You can read it and pat yourself on the back for all the literary in-jokes that you get.

But even while the humor in all of these imagined conversations is somewhat of the same vein–the wildly erratic character playing off the dubious, slightly sarcastic straight man–the satire is smart. Ortberg pokes fun at but also provokes the act of literary analysis, deepening the interpretation of a character by reframing their struggles, their self-expression, and mining the tensions of the original work. The conceit would make a fun exercise for students in a literature class, but the appropriation also pushes for a deeper understanding of a character and a text. In some, like Nancy Drew or the American Girl spoofs, the characters don’t accommodate probing very deep or very far. But Hamlet allowing Gertrude to bring a sandwich up to his room, tuna fish with no relish, suggests that the Dane’s famous melancholy has a tone of adolescent moodiness rather than the existential depth which reverential critics attribute to the play. And Jake’s sexting harangue of a more composed Brett puts a new angle on the sexual tension usually read into The Sun Also Rises.

Perhaps I am just easily surprised, but the realignments in these cases struck me as provocative rather than glib. Ortberg’s playful adaptations show that nothing about so-called “great’ literature is sacred, neither its traditions nor the humanizing power it is often accorded. Nor does the power of literary interpretation belong to over-educated, pompous academics (like yours truly) who intone sententious things in the language of their favorite literary theory. “Great” literature endures because these characters are fascinating, we understand their conflicts, and their inner worlds are not so unlike ours. Even while she makes fun of them, Ortberg shows us why we need to keep reading (and teaching) the classics, why our great literary traditions need to remain accessible, and also why, rather than approaching with awe, our understanding might be improved if we can regard these landmark figures and their works in a spirit of wit, ironic play, humor, and fun.