This first installment of Bennett’s new Debutante Diaries series is a perfectly delightful pastel watercolor of a historical romance and a perfectly unobjectionable entry into a genre that is defined by plucky, kind-hearted heroines, dashing, faintly disheveled heroes, stately ancestral homes, a cast of assorted titled characters, and a scenic Britain that is always sunny.

First Earl I See Tonight ticks all the right boxes for a pleasant read and a feel-good romance. There are family attachment and parental issues to which any reader can relate; there are pretty dresses and big houses, expensive gardens and fancy balls peppered with handsome, titled men; there are the requisite girlfriends (here, a sister and best friend) to help arm and guide the heroine in her path toward winning the hero; there are sad incidents in our characters’ pasts which they nobly overcome; and there is the quirky schoolteacher, Miss Haywinkle, who comes in for a lot of ridicule. All the love scenes, which are delivered in a timely and expected fashion, are affectionate, consensual, and focus on the heroine’s pleasure as well as her sexual education. The wounded, reserved hero is healed by heroine’s love, coming to realize that of course he cannot live without this lovely, perfectly pleasant, entirely unobjectionable girl.

First Earl I See Tonight ticks all the right boxes for a pleasant read and a feel-good romance. There are family attachment and parental issues to which any reader can relate; there are pretty dresses and big houses, expensive gardens and fancy balls peppered with handsome, titled men; there are the requisite girlfriends (here, a sister and best friend) to help arm and guide the heroine in her path toward winning the hero; there are sad incidents in our characters’ pasts which they nobly overcome; and there is the quirky schoolteacher, Miss Haywinkle, who comes in for a lot of ridicule. All the love scenes, which are delivered in a timely and expected fashion, are affectionate, consensual, and focus on the heroine’s pleasure as well as her sexual education. The wounded, reserved hero is healed by heroine’s love, coming to realize that of course he cannot live without this lovely, perfectly pleasant, entirely unobjectionable girl.

I can find nothing to complain about except the fact that First Earl conforms so entirely to the genre as to be—well, generic. I feel like I’ve read this perfectly unobjectionable, pleasant story 100 times before.

This feels like an unfair assessment, because in fact Bennett’s is a very competent entry into this long-loved, time-honored stable. The series device is adorable: the girls challenge each other to keep a diary of their conquests, presumably to share titillating stories of fan flirting, dancing, and perhaps even stolen kisses. Fiona’s entries betray a lively and somewhat disappointed voice as she compares the reality to what she was promised. The hook is compelling, too. Fiona Hartley, the eldest daughter of a wealthy mill owner (what kinds of mills isn’t mentioned), isn’t exactly a huge success in this, her first season. And she doesn’t have the luxury of watching men line up to court her, because she has to arrange her marriage herself.

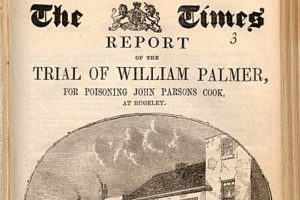

You see, Fiona is being blackmailed by a mysterious stranger who professes to know the secret of her adopted sister Lily’s birth. If Fiona doesn’t pay him five thousand pounds (about the same as asking an heiress nowadays to float you half a mil), he’ll print this information in London’s infamous gossip rag, the Hearsay, and Lily’s prospects for marriage will be utterly ruined. Fiona, being a noble-hearted sort of girl, decides to sacrifice herself; she will propose a hasty union to a likely groom so that she can claim her dowry money, pay off the blackmailer, and then presumably live the rest of her life in a loveless marriage, satisfied in knowing that she has protected her sister, even though the blackmailer would continue to have this damaging information and could employ it at any time.

What? It’s a solid inciting incident. Never mind asking why a blackmailer would approach a young woman of no means of her own rather than, say, her very wealthy father. Or why a parent who adopted a daughter left on the doorstep would later find himself ruined by the revelation of this child’s parentage, which one would not really expect to be high or even respectable. Though no one has been lying from the beginning about Lily’s birth (Fiona considers her a real sister, but knows she was adopted), Fiona is utterly convinced that revelation of her base birth would make Lily ineligible for marriage and thus leave her without hope of any sort of future at all. Because a good marriage is the only possible career option for upper middle-class, gently bred girl. Even though her father is supposed to be wealthy and could presumably offer a dowry that could overcome objections to her birth to a man able to see past them. Or Lily could be perfectly happy with a husband who offers marriage for her own sweet self and not on account of her parentage or dowry. Never mind all that; Fiona has to find a husband.

So she proposes to Gray, the Earl of Ravenport. He seems like a nice man. He helped her when she tripped and crashed into the orchestra pit at the Millbrook ball. Don’t ask why an upper middle-class mill owner’s daughter is being invited to parties thrown by the Upper Ten Thousand; they just are. Gray has recently been cruelly jilted by Helena, so he ought to be on the rebound. Plus, he’s not hard to look at, does not appear to be a gambler or a sot, and seems in all ways presentable. Fiona could probably tolerate a lifelong loveless marriage with him. Sure, he’s an earl, but class differences don’t matter, not here.

Yet Gray, despite being in need of funds to restore the crumbling family seat he calls The Fortress, politely declines this young heiress promising to give herself and her dowry to him. You see, Gray is incapable of love. He has been so wounded by a tragic incident in his childhood, and the loss of his parents, that he does not ever expect to have a functional adult relationship. So, though time is ticking for him to restore The Fortress to its former glory before his adored grandmother goes blind and can’t see any of it, no, he won’t marry Fiona, and will nobly resist her adorable advances.

If you don’t spend time puzzling over the characters’ motivations, the action is fun. Fiona has to try to win over Gray, and their first kiss is disastrous, considering she doesn’t know how to kiss. Gray invites her family to a house party so that the terrible state of the house will scare her off. Fiona is of course charmed by the wild state of the gardens, and draws them; she is an artist of some talent. She won’t be put off by things like crumbling plaster or cracked windows; time is ticking for her, too, and darling Lily’s future is at stake. When she realizes that despite his stated objections, Gray is attracted to her, Fiona uses her sketching as a reason to spend time alone with him, with expected results.

Bennett tries to signal that Gray is attracted by Fiona’s artistic vision, her warm-heartedness, her direct manner and slightly dorky ways, but it appears to be physical attraction that rules him. Gray’s facility with his own emotions doesn’t extend past thinking in expletives when he realizes that he is, in fact, having feelings. (No need to quote them here; you know what they are.) Fiona, despite being a sheltered miss, is a willing participant; after all, she not only has to secure his agreement to marriage, but she also needs something to write about in her diary. Their romantic encounters are given spice by the addition of a mermaid statue, an archery contest, a rowboat, and a rope swing. There’s also that time when Fiona spies on Gray while he fixes a fence. (Earls, in this world, do manual labor. Shirtless.)

The discovery of the blackmailer’s identity is rather quick, and the identity disappointing in terms of the story. Fiona’s eventual change in tactics has a little bit of the “well, duh” about it for the modern reader; beyond that, she has no arc of her own, and she never wavers in her determination to make sacrifices that might potentially injure others without asking them how they feel about it. Gray, as is typical for the brooding wounded heroes of this genre, engages in the conventional sentimental progression from physical desire to romantic love to patriarchal protector, but only after a wiser older relative sets him straight. Betrayals are easy, but also easily resolved.

There’s also no sense of a real time or place at work here; who knows, or cares, where the Hartley mills are, where The Fortress is located, or which monarch is on the throne. Then there’s my odd yet ongoing sense that the characters lack development or even, well, character; the supporting cast all hit their single note, and even for the main characters, motivations are pat when they don’t feel slippery. There’s not any real sense of change or emotional growth for the characters; their path to their HEA is charted from the first, and they hit all the expected advanced and obstacles right on cue.

And why shouldn’t they? This is a pleasant start to what will no doubt be a pleasant series, as Lily and their friend Sophie venture off to snare their own handsome, slightly disheveled, titled men in a series of perfectly timed formulaic beats. It’s my own fault that I long for historical romance that offers me a HEA with a little more grit—the unconventional heroes of Katherine Ashe, the indomitable and resourceful heroines of Sarah MacLean, the glance at real issues as in Maya Rodale, or the sense I always get from a Loretta Chase book that too distinct characters born of a distinct time and place have found the one person who could possible be fit for them, and their love story is the more engaging because of it. If I want my historical romances to have a little more attention to an actual time and place and the cultural attitudes that prevailed within them, a little more historical detail for texture if not character and plot, I guess I’ll just have to go write my own.