Depending on how you look at it, feminism has either become more acceptable and mainstream, or it continues to be perceived by most young women as a radical dogma that requires one to forego personal grooming and to revile men. Feminism is either strong, better, more pervasive than ever before, or it’s been hijacked into a marketing ploy that “liberates” young women by insisting they express themselves by the clothes, make-up, and accessories they buy and wear. Second-wave feminism is dead but third- and fourth-wave feminism are thriving. Wave feminism is archaic and waveless feminism is the thing. Feminism is a global cause or Western feminists have to be very careful about how they try to foist their imperialistic views on others. Feminists are still mainly white and ignorant of the battles of their less privileged sisters. Intersectionality is where it’s at. The future face of feminism is young, multi-colored, and somewhere outside the restrictive gender binary. Feminism is everywhere. Feminism is you.

Depending on how you look at it, feminism has either become more acceptable and mainstream, or it continues to be perceived by most young women as a radical dogma that requires one to forego personal grooming and to revile men. Feminism is either strong, better, more pervasive than ever before, or it’s been hijacked into a marketing ploy that “liberates” young women by insisting they express themselves by the clothes, make-up, and accessories they buy and wear. Second-wave feminism is dead but third- and fourth-wave feminism are thriving. Wave feminism is archaic and waveless feminism is the thing. Feminism is a global cause or Western feminists have to be very careful about how they try to foist their imperialistic views on others. Feminists are still mainly white and ignorant of the battles of their less privileged sisters. Intersectionality is where it’s at. The future face of feminism is young, multi-colored, and somewhere outside the restrictive gender binary. Feminism is everywhere. Feminism is you.

I think all these discussions are delightful. I love reading about them and participating in them. But sometimes, one feels like the ground is ever-shifting. What does feminism even mean these days? What does it signal if I identify as a feminist? What does it require of me? Can I march for my sisters, or do I need to let my sisters speak for themselves? Do I need to feel ashamed of my white, upper-middle-class, highly-educated privilege? Do I need to rebuke the women standing in the same echelon who say they don’t need to march because they don’t see inequality? That if women are being held back, it’s their own choice?

Okay, that last one is easy. I think a rebuke is definitely called for in the last instance. Better yet, I will direct the privileged sister to read Dina Leygerman’s great blog post, “You Are Not Equal, I’m Sorry,” captured on Medium. You don’t have to march, she’s saying, but a polite “thank you” to the women who suffered and fought so you could be ignorant of your own privilege and the forces still holding back other women is not out of line.

Okay, that last one is easy. I think a rebuke is definitely called for in the last instance. Better yet, I will direct the privileged sister to read Dina Leygerman’s great blog post, “You Are Not Equal, I’m Sorry,” captured on Medium. You don’t have to march, she’s saying, but a polite “thank you” to the women who suffered and fought so you could be ignorant of your own privilege and the forces still holding back other women is not out of line.

And for those who are wondering how, if the fight has been going on for over 40 years, we’re not further along in the spectrum toward equality for all genders, there is an excellent explanation offered in historian Marjorie J. Spruill’s new book, Divided We Stand.

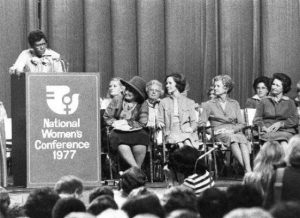

This is a dense book aimed at fellow feminist historians, but it’s a huge contribution to the history of second-wave feminism in the United States, and an absolute must-read for anyone interested in how the wave got halted and the different camps, feminist vs. anti-feminist, so divisively bitter. Spruill begins with the dramatic assessment that the National Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas, in 1977 was a dramatic watershed moment in the advance of women’s rights in the United States, and she spends the bulk of the book in a detailed inquiry of what led up to the conference, and what happened there, with the last segments devoted to a summation of what has happened for women’s rights in this country between then and now.

This is a dense book aimed at fellow feminist historians, but it’s a huge contribution to the history of second-wave feminism in the United States, and an absolute must-read for anyone interested in how the wave got halted and the different camps, feminist vs. anti-feminist, so divisively bitter. Spruill begins with the dramatic assessment that the National Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas, in 1977 was a dramatic watershed moment in the advance of women’s rights in the United States, and she spends the bulk of the book in a detailed inquiry of what led up to the conference, and what happened there, with the last segments devoted to a summation of what has happened for women’s rights in this country between then and now.

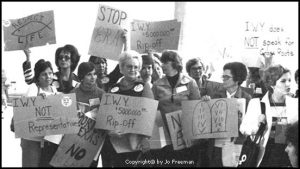

It takes some persuading to the see the NWC as a fundamental accomplishment, especially since Spruill, both times she talks about it–in the introductory chapter, and then in the middle chapters exploring the Houston event–spends at least as much time discussing the anti-feminist, anti-ERA rally taking place alongside, an event that seems to have been louder, better-attended, and even more self-congratulatory. For those curious about what the recent Women’s Marches following Trump’s inauguration have accomplished, this book is a good reminder that protests galvanize, provide solidarity, and develop loyalty among a group. It is also testament to the fact that, when you have two equally heated opinions that are dead-set against one another, nothing gets done beyond a lot of screaming, insult-launching, and exaggerated hyperbole.

It takes some persuading to the see the NWC as a fundamental accomplishment, especially since Spruill, both times she talks about it–in the introductory chapter, and then in the middle chapters exploring the Houston event–spends at least as much time discussing the anti-feminist, anti-ERA rally taking place alongside, an event that seems to have been louder, better-attended, and even more self-congratulatory. For those curious about what the recent Women’s Marches following Trump’s inauguration have accomplished, this book is a good reminder that protests galvanize, provide solidarity, and develop loyalty among a group. It is also testament to the fact that, when you have two equally heated opinions that are dead-set against one another, nothing gets done beyond a lot of screaming, insult-launching, and exaggerated hyperbole.

This is best seen in the chapters devoted to the state conferences preceding the NWC, whose job it was to elect delegates to the national convention and determine a platform to submit. Here there is a tragic arc to the narrative as well. While legislative and popular support for the ERA in particular and the idea of women’s rights in particular was high in the initial stages, the conventions did what they were supposed to do: elect a diverse set of delegates and develop a platform that reflected a progressive agenda of full civil rights, including reproductive rights and non-discrimination, for the national platform that would eventually be submitted to the president. Once the anti-ERA forces got into action—the forces who passionately believed that the traditional family structure, with the woman at home dependent on the husband, were the only right model for everyone—the book becomes a wearying account of how, state by state, busloads of smug white evangelical women and their husbands descended on conventions, disrupted any fruitful discussion, congratulated themselves for being family champions, and then went back home to their safe, white houses.

This is best seen in the chapters devoted to the state conferences preceding the NWC, whose job it was to elect delegates to the national convention and determine a platform to submit. Here there is a tragic arc to the narrative as well. While legislative and popular support for the ERA in particular and the idea of women’s rights in particular was high in the initial stages, the conventions did what they were supposed to do: elect a diverse set of delegates and develop a platform that reflected a progressive agenda of full civil rights, including reproductive rights and non-discrimination, for the national platform that would eventually be submitted to the president. Once the anti-ERA forces got into action—the forces who passionately believed that the traditional family structure, with the woman at home dependent on the husband, were the only right model for everyone—the book becomes a wearying account of how, state by state, busloads of smug white evangelical women and their husbands descended on conventions, disrupted any fruitful discussion, congratulated themselves for being family champions, and then went back home to their safe, white houses.

Spruill doesn’t shy away from how the anti-forces deployed all sorts of others groups, including the KKK, to bulk out their protest numbers (an association Schafly always denied). In short, these chapters pound home the point learned from watching the U.S. Congress in action for the last six years: those who can make every effort available to obstruct an agenda that might mean more social justice for the broader population can usually manage to succeed. But the book also doesn’t shy away from showing the divisions within the feminist ranks—the arguments over how far to embrace LGBT rights, for example, and how to handle the abortion question—that led to factions and fissures there that generally left the middle-of-the-road feminists and the pro-life feminists with no place to go. As the more progressive voices won out, some of the middle who weren’t prepared to go that far get left behind—which is why the popular opinion still prevails among my students that feminists are strident, bra-burning, man-hating radicals, which means productive conversations about how to promote equal rights and just treatment for all genders get derailed quickly.

Spruill doesn’t shy away from how the anti-forces deployed all sorts of others groups, including the KKK, to bulk out their protest numbers (an association Schafly always denied). In short, these chapters pound home the point learned from watching the U.S. Congress in action for the last six years: those who can make every effort available to obstruct an agenda that might mean more social justice for the broader population can usually manage to succeed. But the book also doesn’t shy away from showing the divisions within the feminist ranks—the arguments over how far to embrace LGBT rights, for example, and how to handle the abortion question—that led to factions and fissures there that generally left the middle-of-the-road feminists and the pro-life feminists with no place to go. As the more progressive voices won out, some of the middle who weren’t prepared to go that far get left behind—which is why the popular opinion still prevails among my students that feminists are strident, bra-burning, man-hating radicals, which means productive conversations about how to promote equal rights and just treatment for all genders get derailed quickly.

Spruill’s research is excellent and her prose, for the most part, is up to the task of handling the many threads of her narrative. There are some places where her overviews descend into roll calls of who was at a certain meeting or who supported a certain piece of legislation; there are other places where the narrative seems to switch back and forth in time, and one goes over ground that already felt covered. These are small drawbacks to what otherwise is a sharp, smart, very well-organized assessment of just what the feminist were fighting for, and what their opponents were fighting against. She is fair to both sides, quotes scrupulously and at length from her primary research, and also managed to interview many of the major figures on their involvement.

The major women on the scene emerge as courageous, charismatic, dedicated, impressive people, among them Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan (all pro-ERA), and Phyllis Schafly (anti). The story of how Schafly nearly single-handedly organized the resistance and halted such an enormously important piece of legislation as equal rights for all genders is awesome and—if you happen to be on the side of equal rights for women—a completely demoralizing example of how the shrill misuse of information and incitement of fear can stop any real dialogue and any positive change from happening (something we continue to see happening in the discussion on women’s rights up to this day). In this way, Spruill’s history is a revealing and explanatory account of just how the divisions between the progressives and the conservatives got so deep and the rhetoric got so heated to the point that there seems no middle ground remaining.

The major women on the scene emerge as courageous, charismatic, dedicated, impressive people, among them Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan (all pro-ERA), and Phyllis Schafly (anti). The story of how Schafly nearly single-handedly organized the resistance and halted such an enormously important piece of legislation as equal rights for all genders is awesome and—if you happen to be on the side of equal rights for women—a completely demoralizing example of how the shrill misuse of information and incitement of fear can stop any real dialogue and any positive change from happening (something we continue to see happening in the discussion on women’s rights up to this day). In this way, Spruill’s history is a revealing and explanatory account of just how the divisions between the progressives and the conservatives got so deep and the rhetoric got so heated to the point that there seems no middle ground remaining.

After the last chapters, which are a fast summary of how rights for women have swung back and forth depending on whether the administration was led by a Republican or a Democrat, it’s hard to see a way forward, and Spruill doesn’t really devote herself to solutions. However, she’s laid a careful, solid, even foundation for future investigations of feminist history and women’s rights in the US. Let’s hope she’s also laid the ground for an intelligent discussion of solutions and, perhaps, even without an ERA, a national acceptance of the belief that women are in fact equal to full human, constitutional, civil rights and equal treatment under the law. I hope I live to see that day.